Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Categorical Perception and Knowledge

?

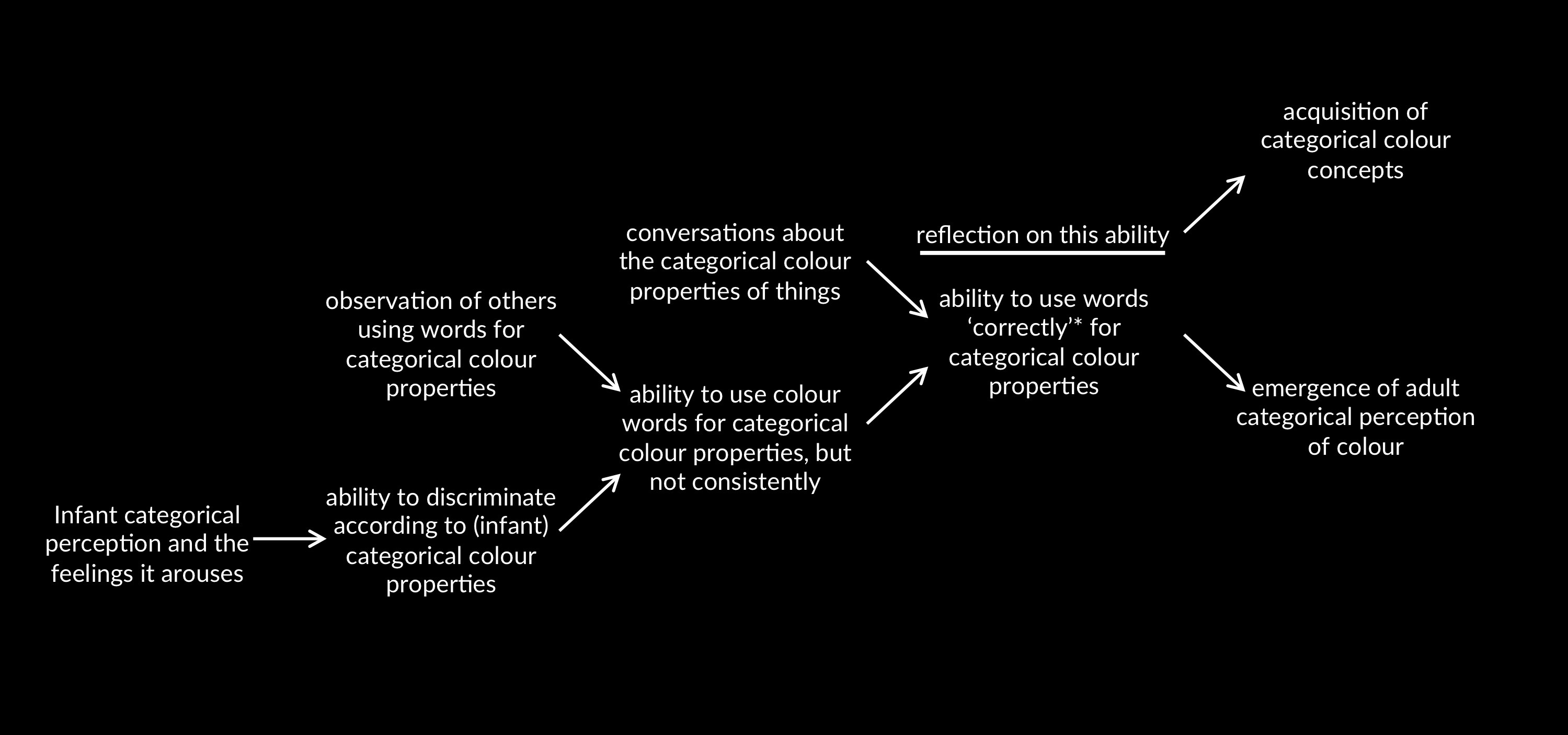

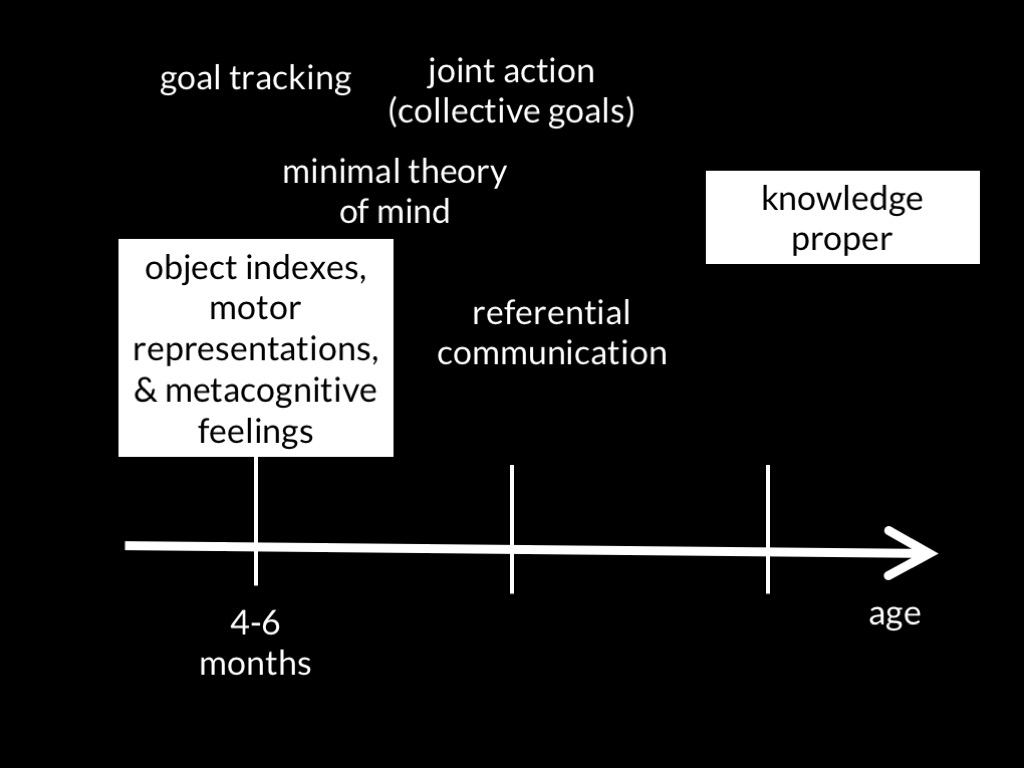

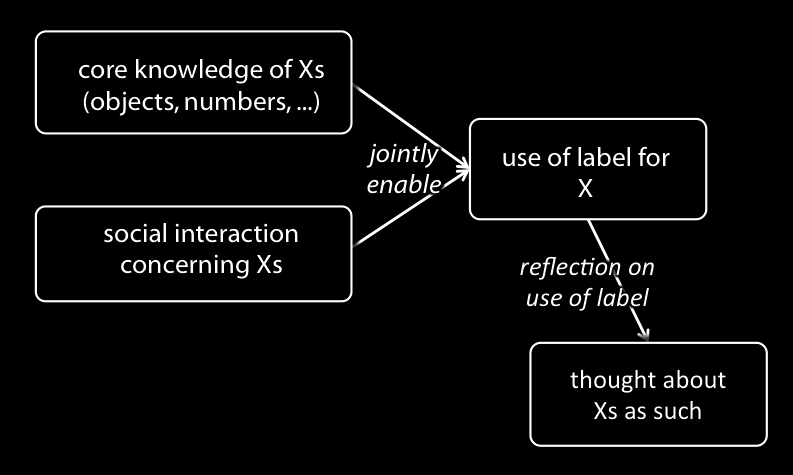

How is categorical perception involved in the emergence of the knowledge of colours of things?

Categorical perception provides ‘the building blocks—the elementary units—for higher-order categories’

Harnad, 1987 p. 3

‘The building blocks of all our complex representations are the representations that are constructed from individual core knowledge systems.’

Spelke, 2003: 307

View 1 : Having categorical perception of colour (or X) amounts to having colour (or X) concepts.

‘The module … automatically provides a conceptual identification of its input for central thought … in exactly the right format for inferential processes’

(Leslie 1988: 193-4)

Is this right?

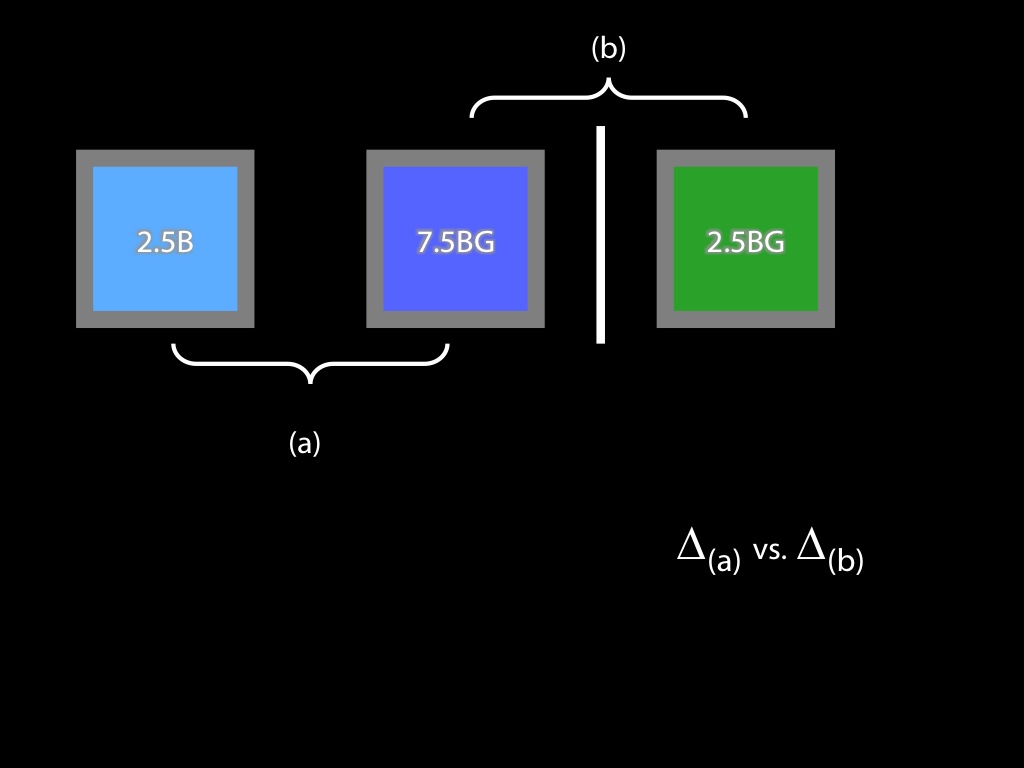

Which one of these is like the toy I just put away?

Kowalski and Zimiles, 2006 Experiment 2

Acquiring colour concepts depends on acquiring colour words.

‘the course of acquisition for color is protracted and errorful’

Sandhofer and Thom, 2006

NO

View 1 : Having categorical perception of colour (or X) amounts to having colour (or X) concepts.

‘The module … automatically provides a conceptual identification of its input for central thought … in exactly the right format for inferential processes’

(Leslie 1988: 193-4)

Is this right?

View 2 : redescription

‘the earliest conceptual functioning consists of a redescription of perceptual structure’

(Mandler 1992)

Is this right?

The extensions of colour terms vary between languages.

(E.g. Russian colour terms include ‘goluboy’ (for lighter blues) and ‘siniy’ (for darker blues).)

English

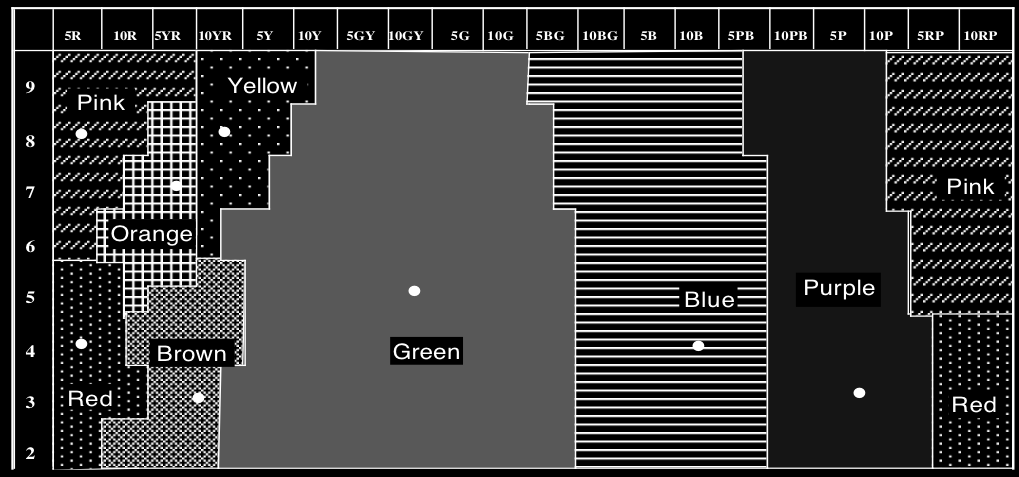

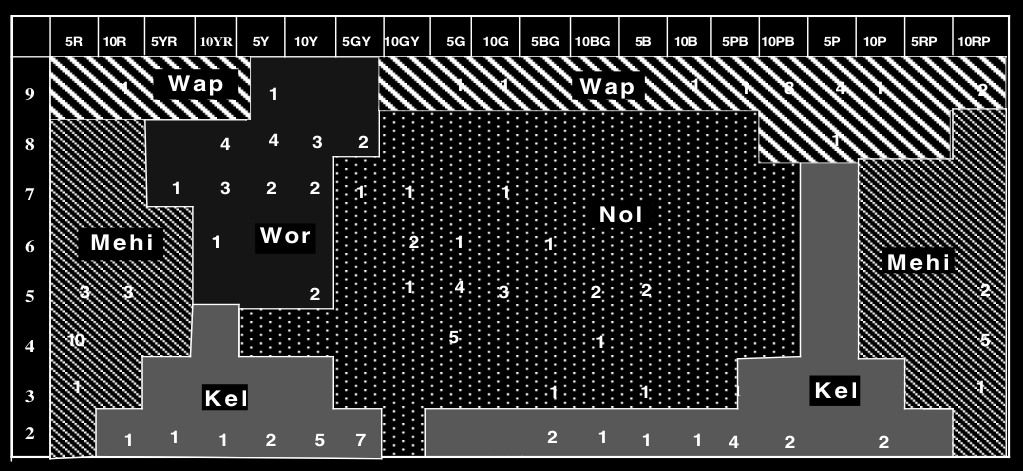

Roberson & Hanley 2010, Figure 1c

Berinmo

Roberson & Hanley 2010, Figure 1b

The extensions of colour terms vary between languages.

(E.g. Russian colour terms include ‘goluboy’ (for lighter blues) and ‘siniy’ (for darker blues).)

Roberson and Hanley, 2007; Winawer et al, 2007

Infants’ and toddlers’ perceptual categories are not influenced by the extensions of colour terms.

Franklin et al, 2005

Therefore:

Infants’ perceptual categories do not match adults’ concepts.

no?

View 2 : redescription

‘the earliest conceptual functioning consists of a redescription of perceptual structure’

(Mandler 1992)

Is this right?

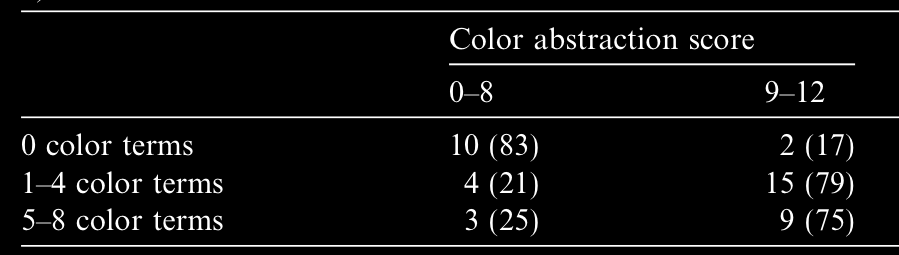

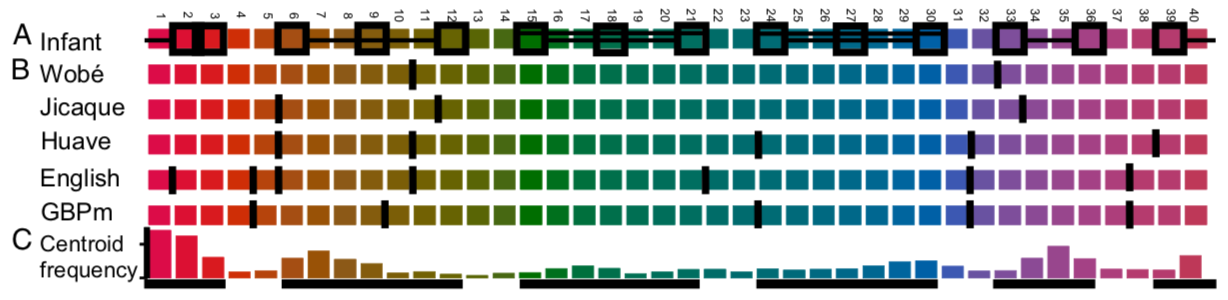

Skelton et al, 2017 figure 1

‘It is not yet clear how exactly categorical responses by infants relate to the categories for basic color terms by adults’

Witzel & Gegenfurtner, 2018 p. 489

maybe

View 2 : redescription

‘the earliest conceptual functioning consists of a redescription of perceptual structure’

(Mandler 1992)

Is this right?

???

Categorical perception provides ‘the building blocks—the elementary units—for higher-order categories’

Harnad 1987, p. 3

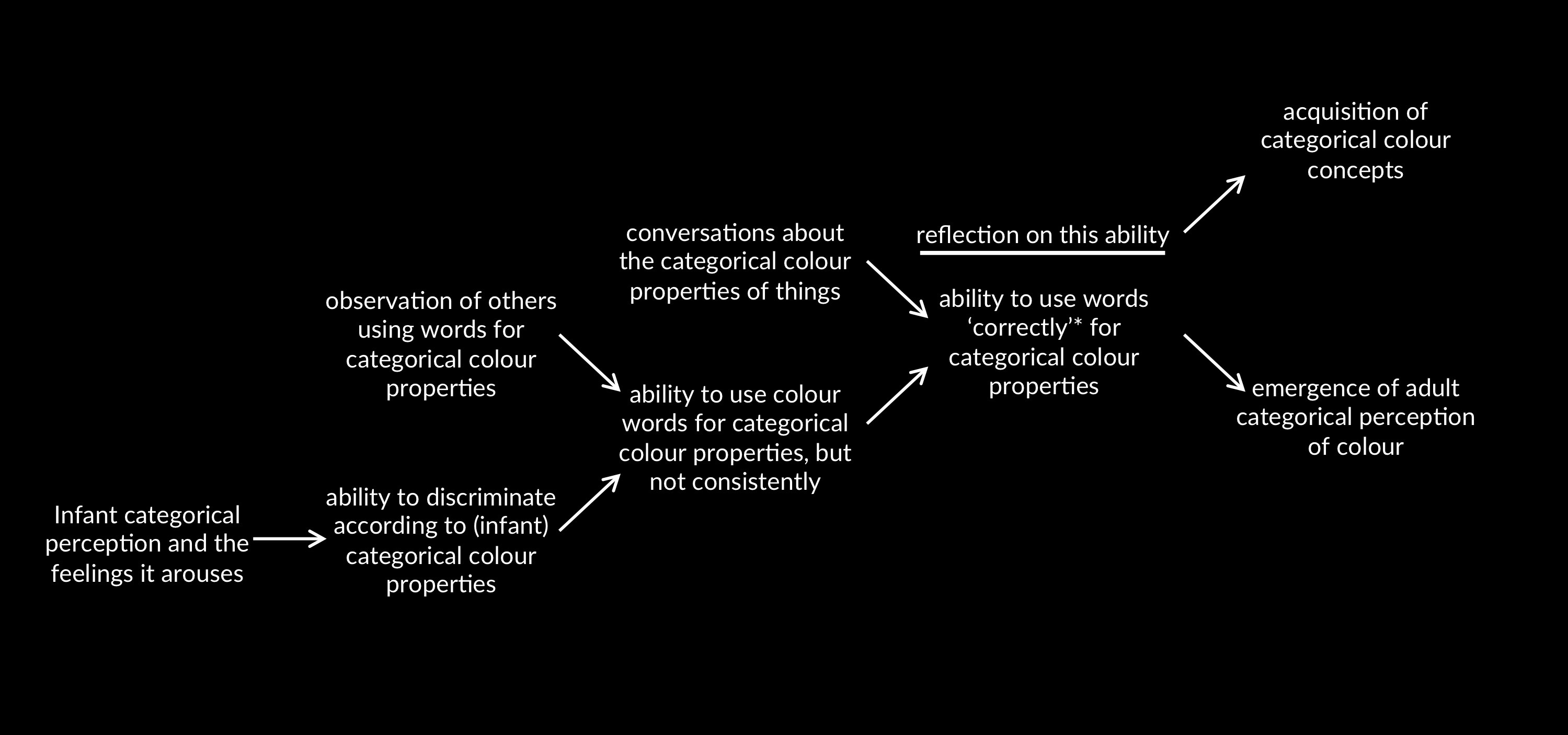

development as (re)discovery

In acquiring a colour concept or word you need to:

- identify the dimension (colour not shape, size, or ...)

- locate the boundaries

In acquiring a colour concept or word you need to:

- identify the dimension (colour not shape, size, or ...)

- locate the boundaries

In acquiring a colour concept or word you need to:

- identify the dimension (colour not shape, size, or ...)

- locate the boundaries

conclusion

building blocks: no; (re)discovery: maybe