Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

From Joint Action to Communication

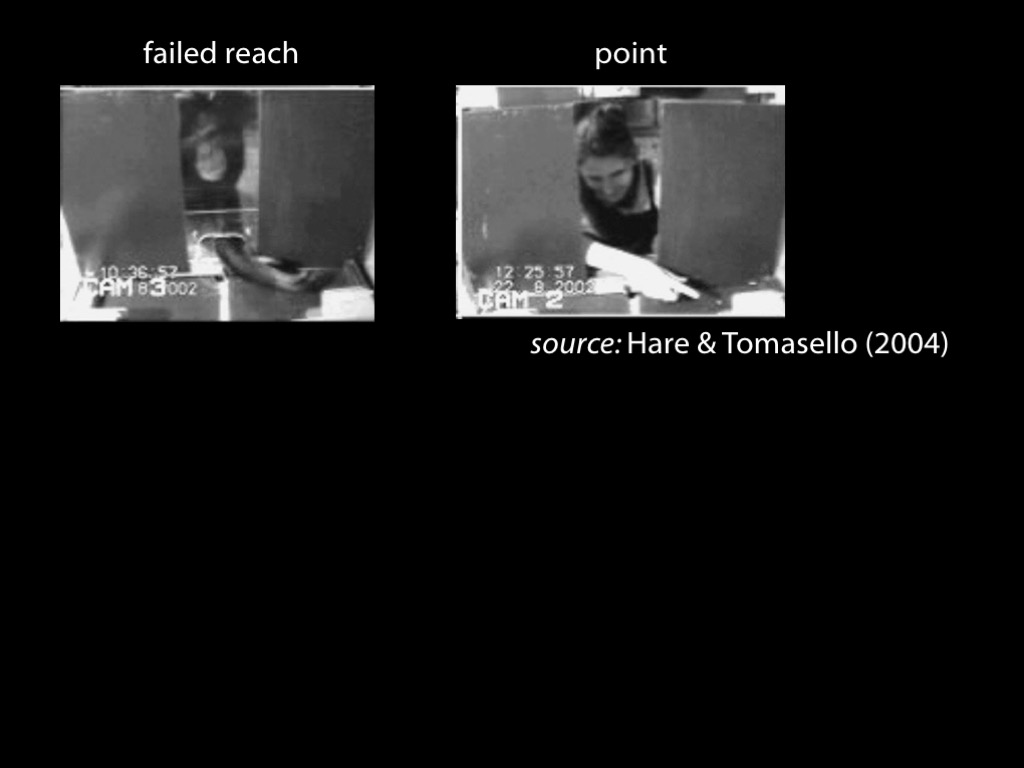

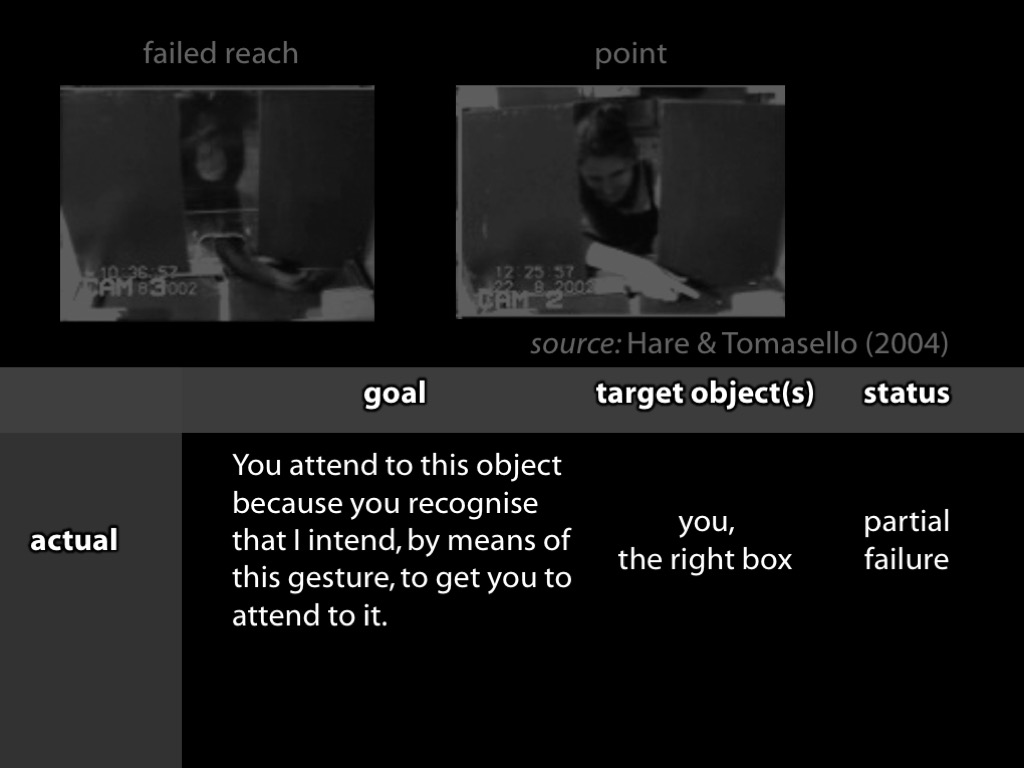

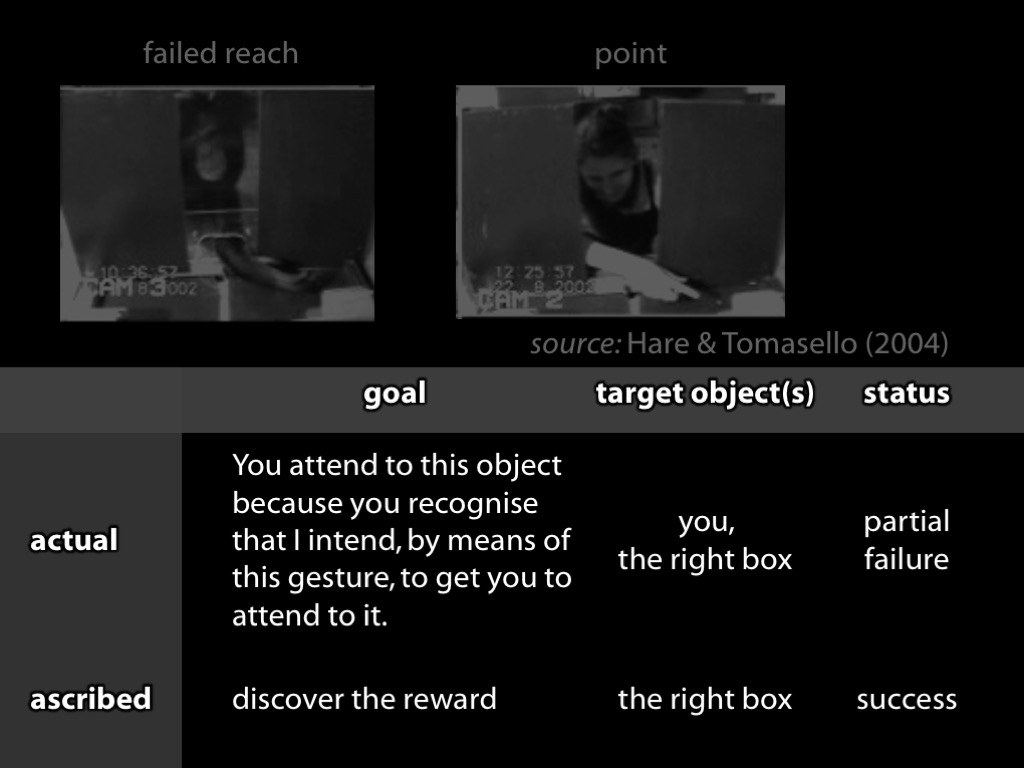

grasping / orienting vs pointing

individual vs joint

production : pointing is done to initiate joint action

objection : infants point when there is no possibility of joint action

(mis)comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

Your-goal-is-my-goal

1. You are about to attempt to engage in some joint action or other with me.

2. I am not about to change the single goal to which my actions will be directed.

Therefore:

3. A goal of your actions will be my goal, the goal I now envisage that my actions will be directed to.

(mis)comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or understanding pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.