Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Origins of Mind : 09

‘participation in cooperative ... interactions … leads children to construct uniquely powerful forms of cognitive representation.’

(Moll & Tomasello 2007)

‘perception, action, and cognition are grounded in social interaction’

(Knoblich & Sebanz 2006)

‘human cognitive abilities … [are] built upon social interaction’

(Sinigaglia and Sparaci 2008)

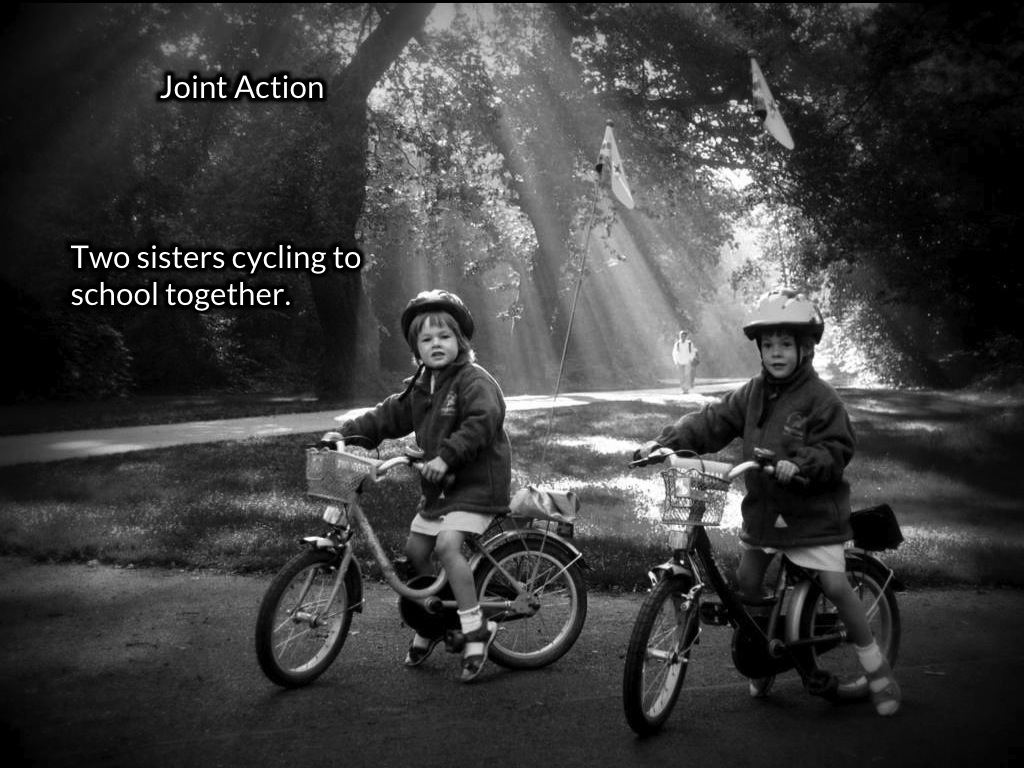

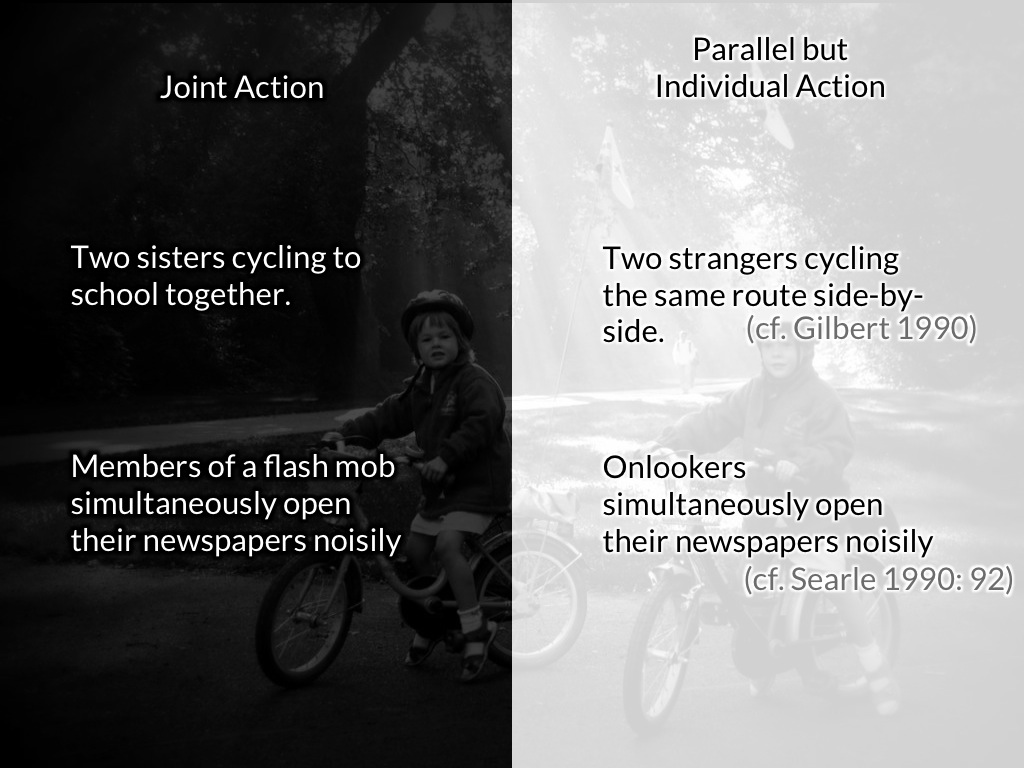

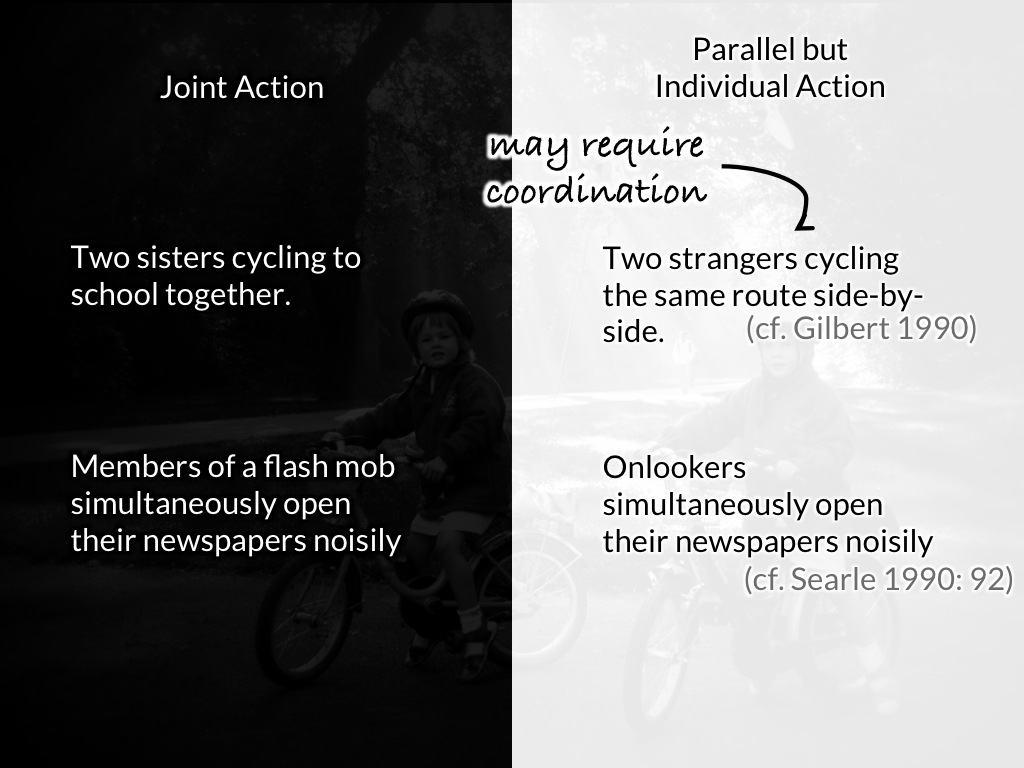

What kinds of social interaction? Joint action!

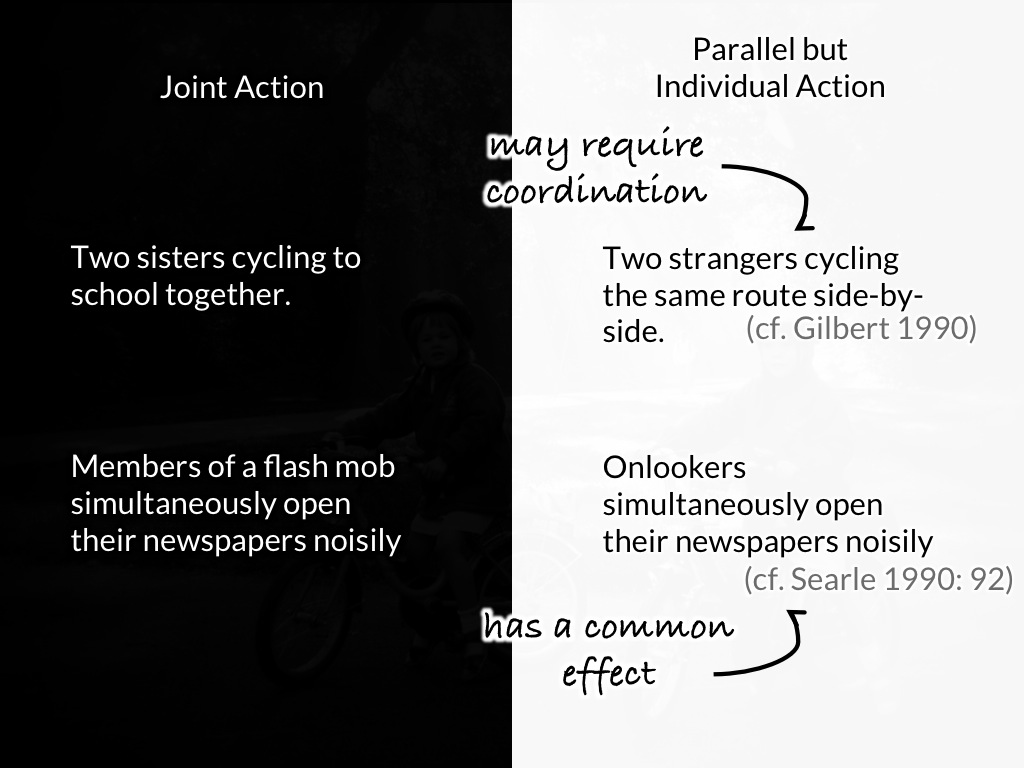

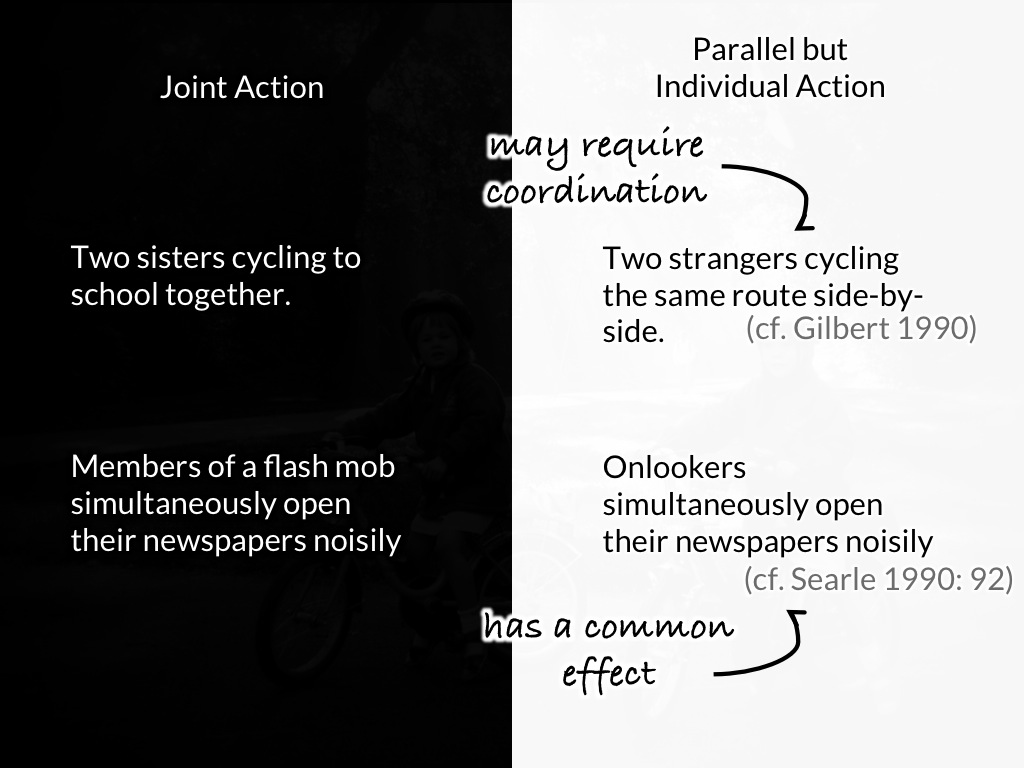

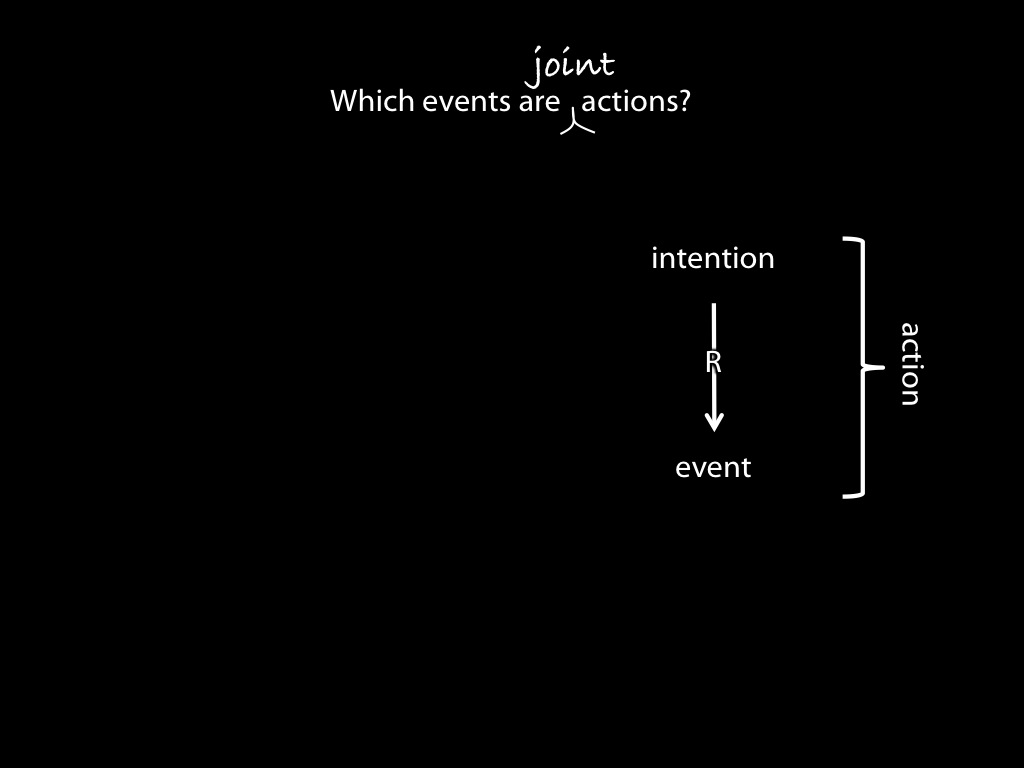

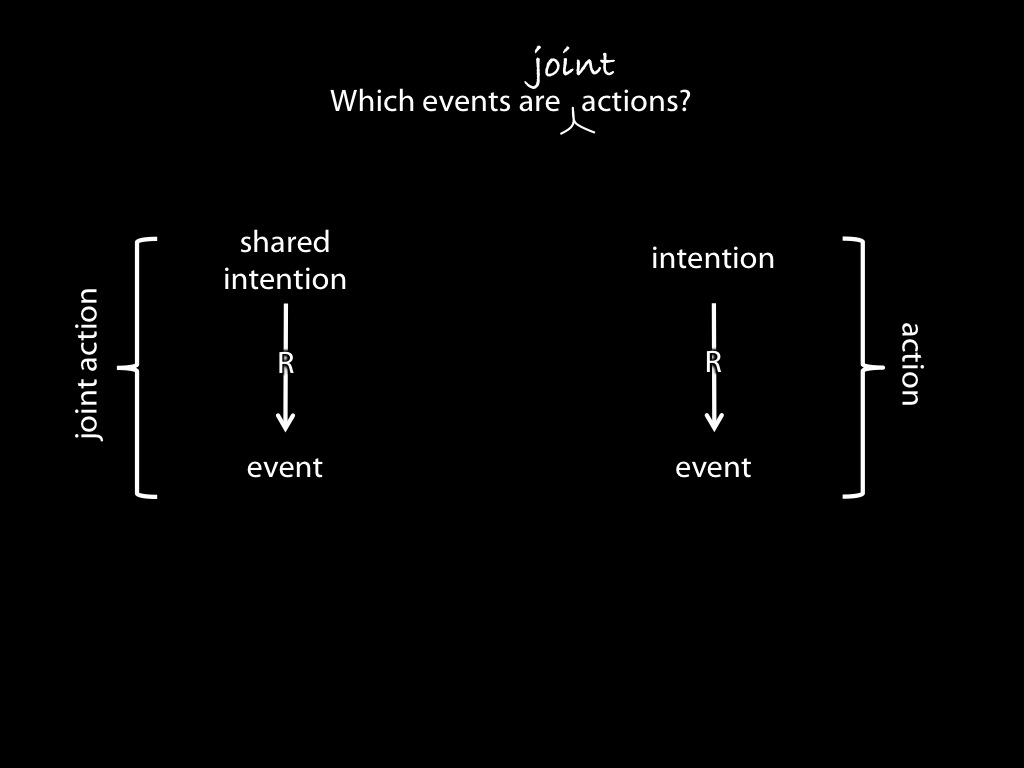

What distingiushes joint action from parallel but merely individual action?

shared intention

‘I take a collective action to involve a collective [shared] intention.’

(Gilbert 2006, p. 5)

‘The sine qua non of collaborative action is a joint goal [shared intention] and a joint commitment’

(Tomasello 2008, p. 181)

‘the key property of joint action lies in its internal component [...] in the participants’ having a “collective” or “shared” intention.’

(Alonso 2009, pp. 444-5)

‘Shared intentionality is the foundation upon which joint action is built.’

(Carpenter 2009, p. 381)

?

shared intention

Carpenter(2009, p. 281)

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

What Joint Action Could Not Be

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

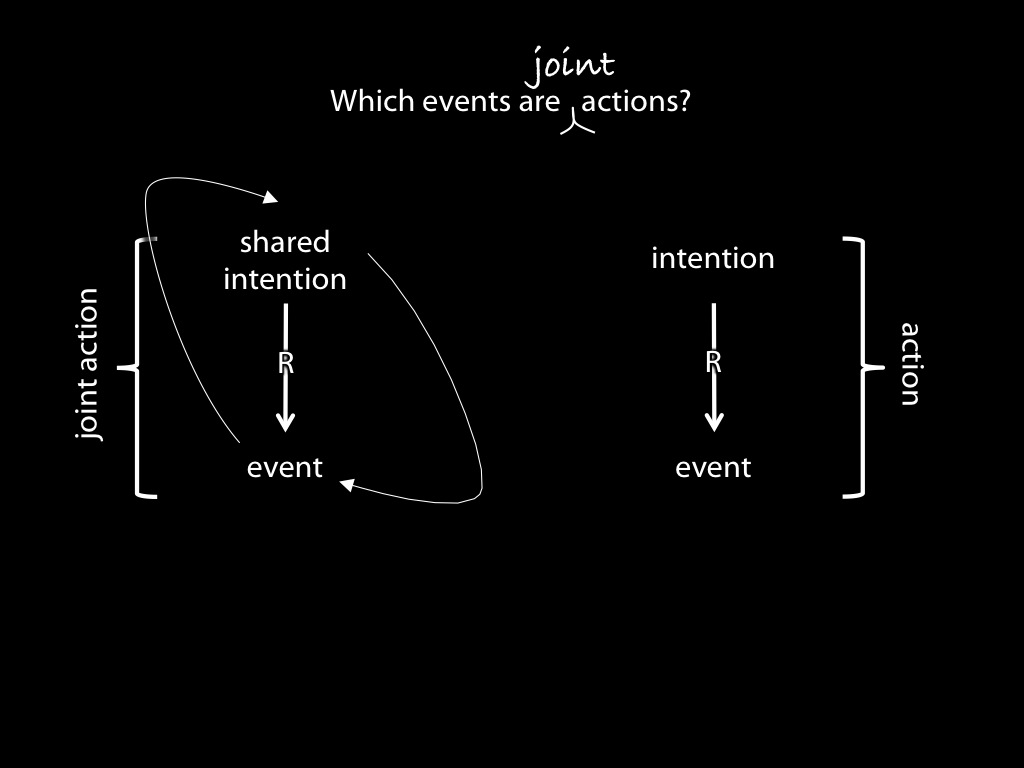

Inconsistent Triad

1. joint action fosters an understanding of minds;

2. all joint action involves shared intention; and

3. a function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans.

Development of Joint Action: Planning

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

‘shared intentional agency [i.e. ‘joint action’] consists, at bottom, in interconnected planning’

Bratman, 2011 p. 11

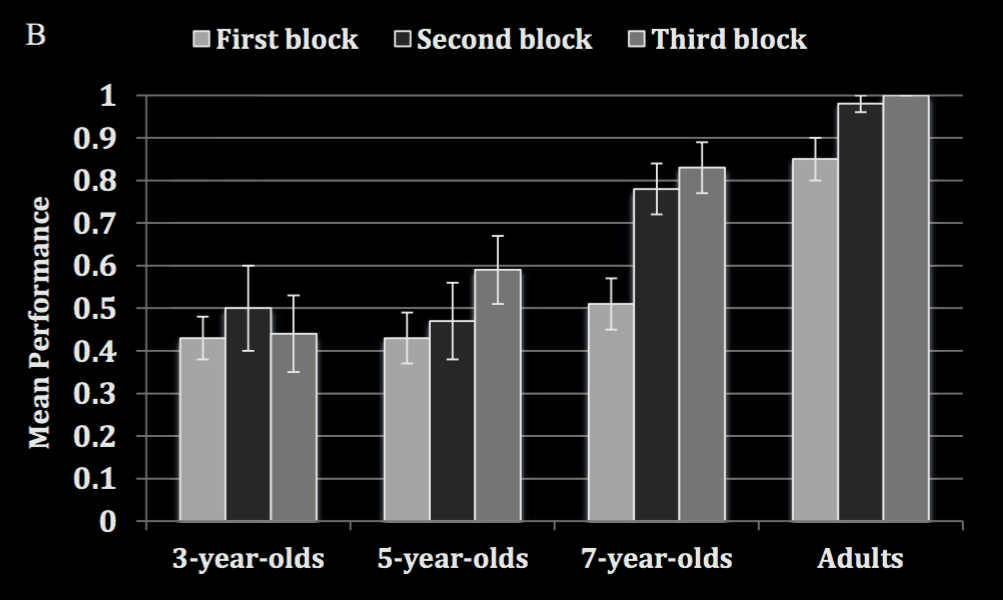

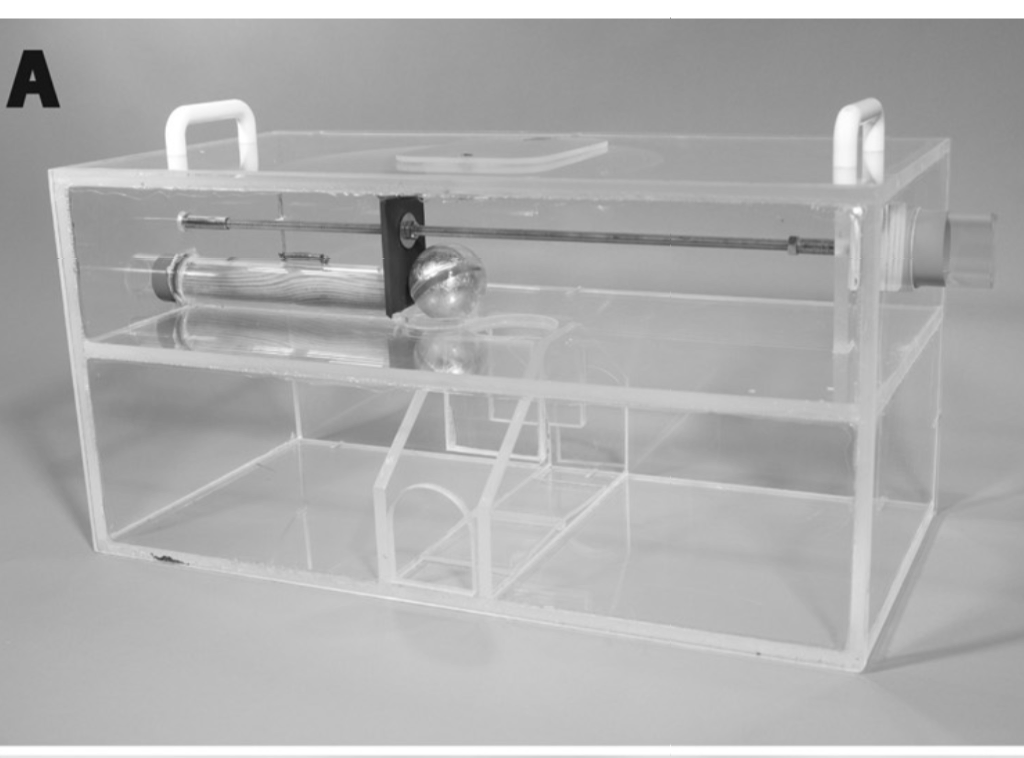

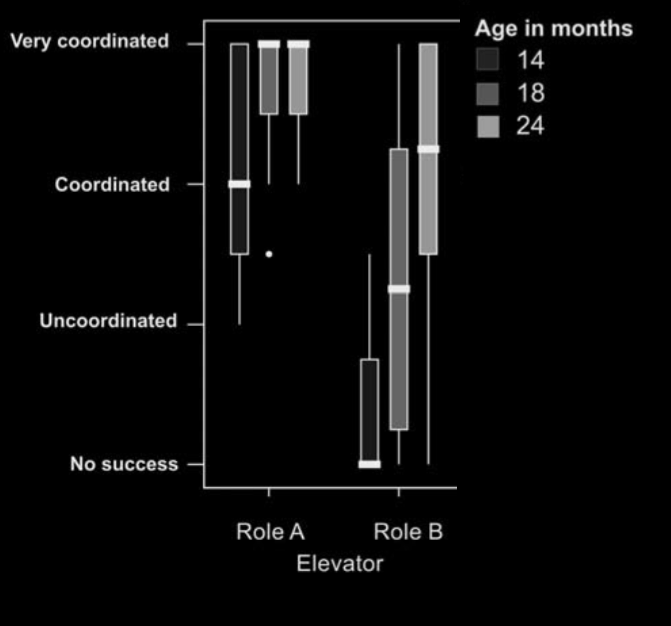

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 1

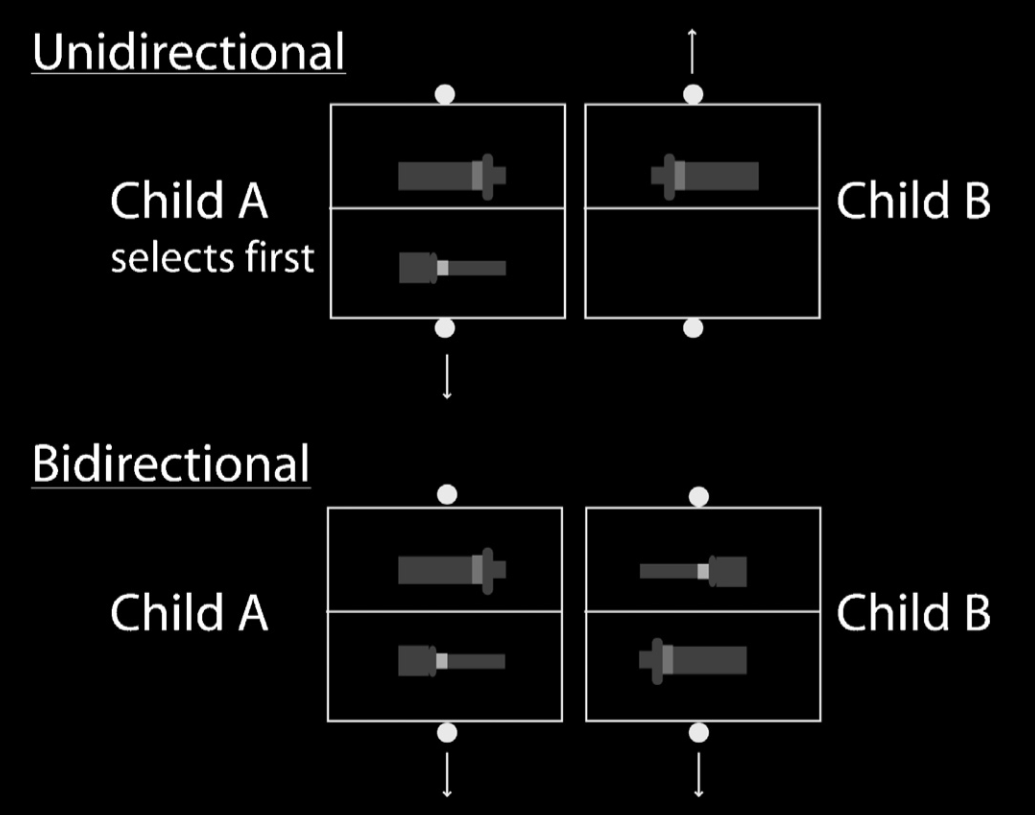

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 2B

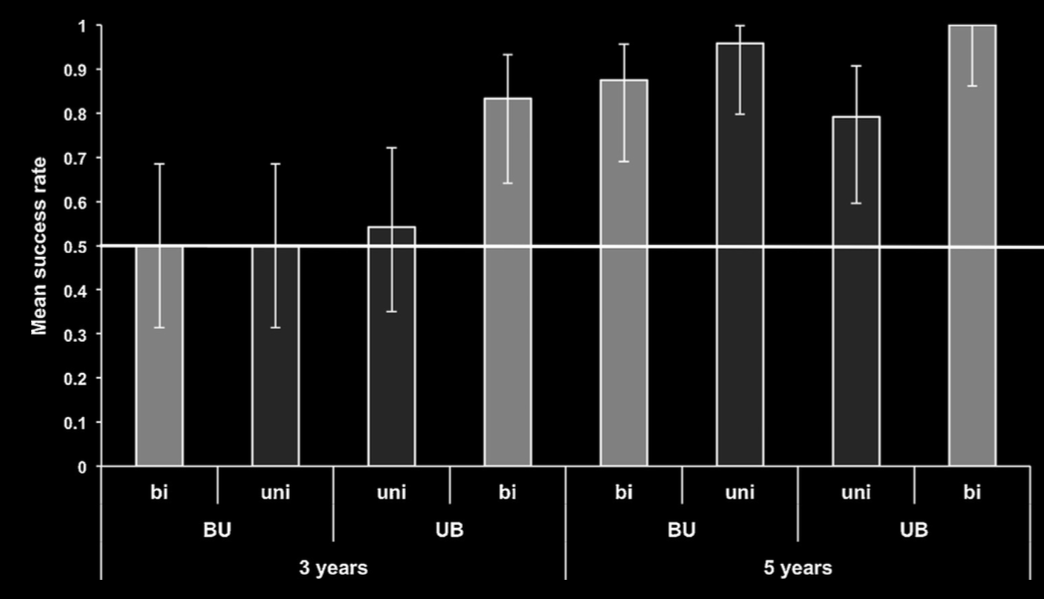

‘3- and 5-year-old children do not consider another person’s actions in their own action planning (while showing action planning when acting alone on the apparatus).

Seven-year-old children and adults however, demonstrated evidence for joint action planning. ... While adult participants demonstrated the presence of joint action planning from the very first trials onward, this was not the case for the 7-year-old children who improved their performance across trials.’

Paulus et al, 2016 p. 1059

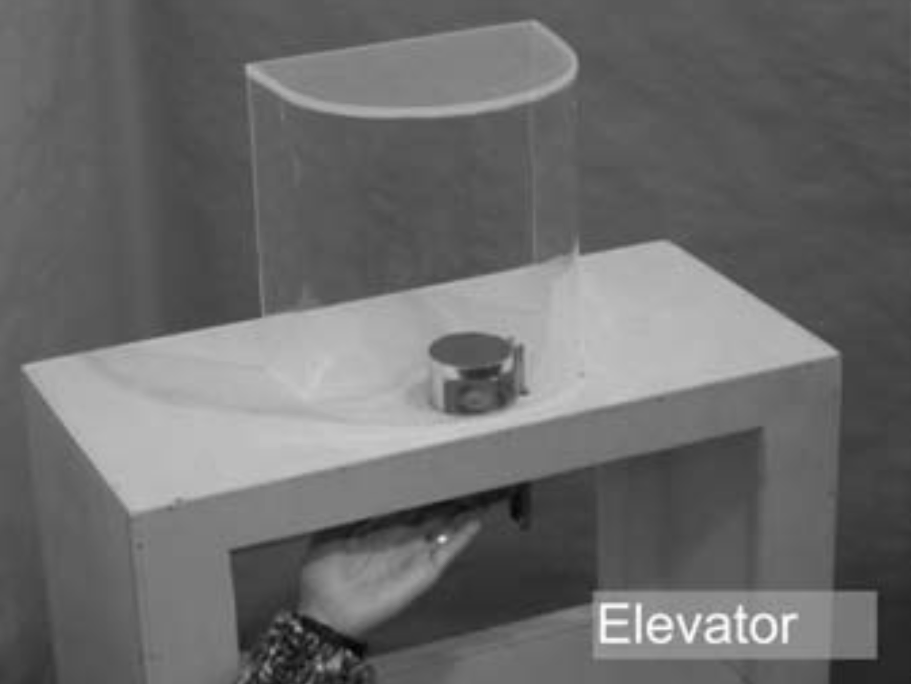

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 1A

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 2

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 3

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Mismatch:

Bratman’s account of joint action

vs

1- to 3-year-olds’ joint action abilities

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

Inconsistent Triad

1. joint action fosters an understanding of minds;

2. all joint action involves shared intention; and

3. a function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans.

Development of Joint Action: Years 1-2

No planning ...

... So which joint actions can one- and two-year-olds perform?

4-6 months

dyadic interactions

6-12 months

triadic interactions

~ 12-24 months

infants initiate and re-start joint actions

e.g. ‘peek-a-boo; tickle; rhythmic games; chase’

Brownell, 2011

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 3 (part)

Joint Action in Years 1-2

In the first and second years of life,

there is joint action

but it does not appear to involve planning agency

or shared intention.

Bratman’s account does not characterise

the sort of joint actions

infants perform in the first and second years of life.

Two-year-olds perform some joint actions but not others.

What distinguishes the joint actions they can perform from those they cannot?

Collective Goals vs Shared Intentions

‘all sorts of joint activity is possible without conscious goal representations, complex reasoning, and advanced self-other understanding ...

In studying its development in children the problem is how to characterize and differentiate primitive, lower levels of joint action operationally from more complex and cognitively sophisticated forms’

Brownell, 2011 p. 195

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers. [causal]

- ambiguous

The goal of their actions was to fill Zach’s glass. [teleological]

- also ambiguous

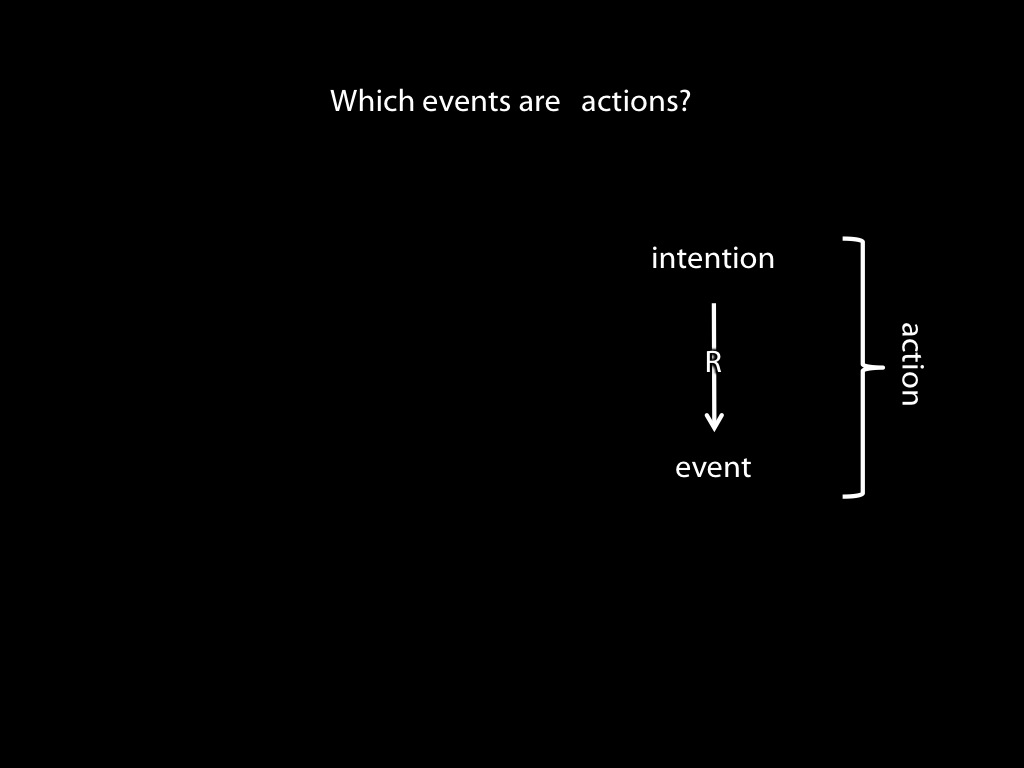

Joint action:

An event involving two or more agents where the agents’ actions have a collective goal.

In virtue of what do actions involving multiple agents ever have collective goals?

Shared Goals

Functional role: coordinate actions

Our actions do, or will, have a collective goal, G, because:

(i) We each expect the other(s) to perform an action directed to G.

(ii) We each expect that if G occurs, it will occur as a common effect of all of our actions.

How?

Joint action explains the emergence of referential communication.