Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Origins of Mind : 10

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

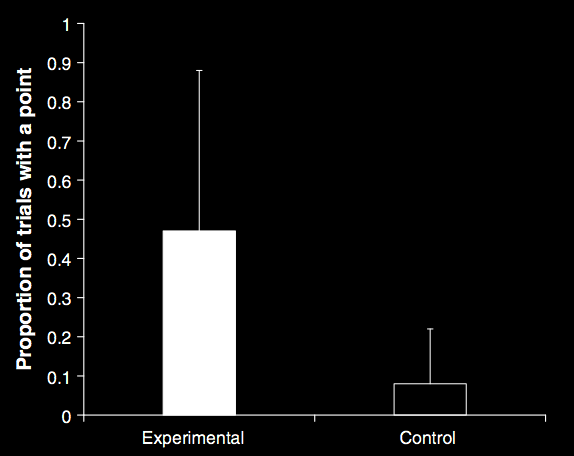

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 3

Liszkowski et al 2008, figure 5

From around 11 or 12 months of age, humans spontaneously use pointing to ...

- request

- inform

- initiate joint engagement (‘Wow! That!’)

A Puzzle about Pointing

How do infants understand pointing actions?

Hypothesis: ‘shared intentionality’ / communicative intention

shared intentionality

‘infant pointing is best understood---on many levels and in many ways---as depending on uniquely human skills and motivations for cooperation and shared intentionality, which enable such things as joint intentions and joint attention in truly collaborative interactions with others (Bratman, 1992; Searle, 1995).’

Tomasello et al (2007, p. 706)

Why suppose this?

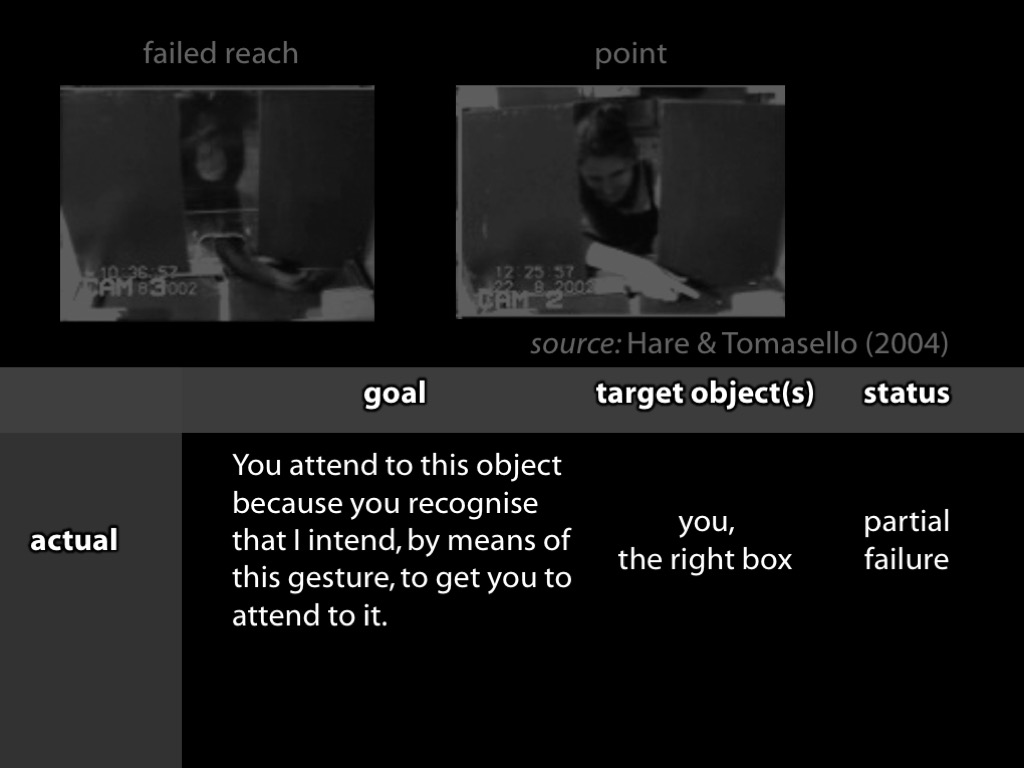

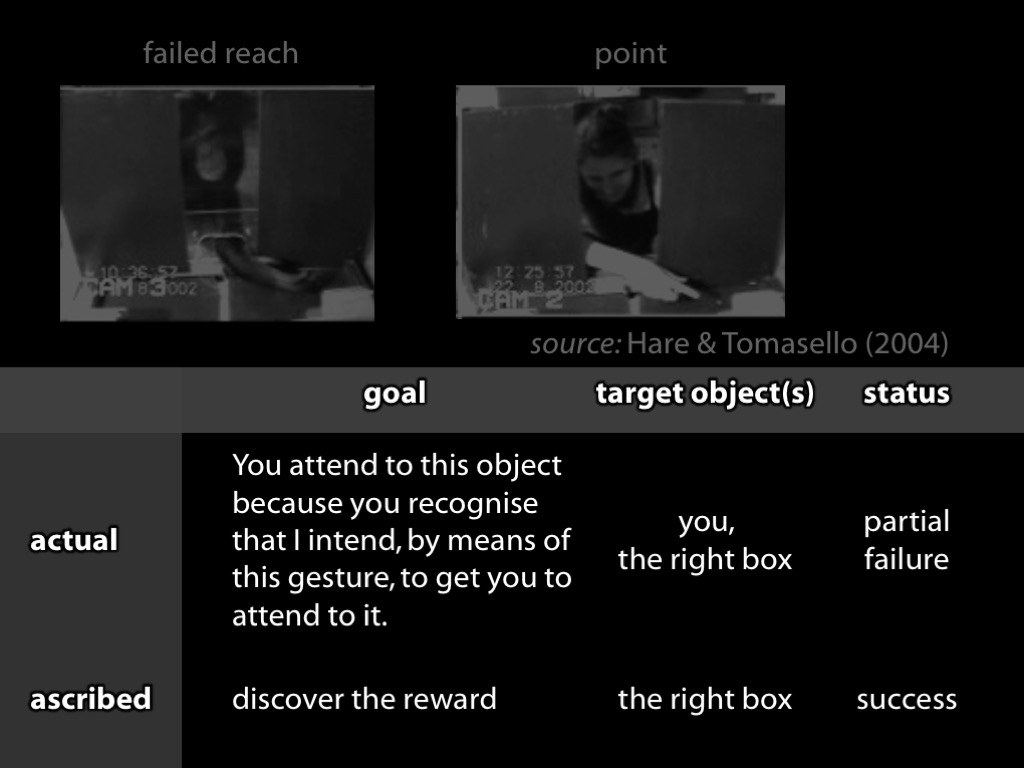

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

What is a communicative action?

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

Hare & Tomasello, 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’

Moll & Tomasello, 2007 p. 6

First approximation: An action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

The confederate means something in pointing at the left box if she intends:

- \item that you open the left box;

- \item that you recognize that she intends (1), that you open the left box; and

- \item that your recognition that she intends (1) will be among your reasons for opening the left box.

(Compare Grice, 1967 p. 151; Neale, 1992 p. 544)

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or understanding pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.

From Joint Action to Communication

grasping / orienting vs pointing

individual vs joint

production : pointing is done to initiate joint action

objection : infants point when there is no possibility of joint action

(mis)comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

Your-goal-is-my-goal

1. You are about to attempt to engage in some joint action or other with me.

2. I am not about to change the single goal to which my actions will be directed.

Therefore:

3. A goal of your actions will be my goal, the goal I now envisage that my actions will be directed to.

(mis)comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

comprehension : in pointing, others engage in joint action with me

Inconsistent tetrad

1. 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

2. Producing or understanding pointing gestures involves understanding communicative actions.

3. A communicative action is an action done with an intention to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

4. Pointing facilitates the developmental emergence of sophisticated cognitive abilities including mindreading.

Conclusions and Questions

the question

In the first year of life

humans already possess a range of sophisticated abilities

which do not involve, and are isolated from, knowledge.

Therefore the transition must be a process of rediscovery.

As this is not something infants could achive alone, rediscovery must be a joint action.

1. models (How are things in the domain related from the point of view of a 3/6/9-month-old?)

2. processes (What links the model to the infant?)

puzzles matter

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| number | --""-- | --""-- |

| syntax | anticipatory looking | [as adults] |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

Core Knowledge

‘there is a third type of conceptual structure,

dubbed “core knowledge” ...

that differs systematically from both

sensory/perceptual representation[s] ... and ... knowledge.’

Carey, 2009 p. 10

Crude Picture of the Mind

- epistemic

(knowledge states) - broadly motoric

(motor representations of outcomes and affordances) - broadly perceptual

(visual, tactual, ... representations; object indexes ...) - metacognitive feelings

(connect the motoric and perceptual to knowledge)

‘if you want to describe what is going on in the head of the child when it has a few words which it utters in appropriate situations, you will fail for lack of the right sort of words of your own.

‘We have many vocabularies for describing nature when we regard it as mindless, and we have a mentalistic vocabulary for describing thought and intentional action; what we lack is a way of describing what is in between’

(Davidson 1999, p. 11)

What is in between:

object indexes

motor representations

metacognitive feelings

...

Minimal approaches

to mindreading, joint action

and referential communication

do not presuppose

and may therefore explain

knowledge knowledge.

development as (re)discovery

end

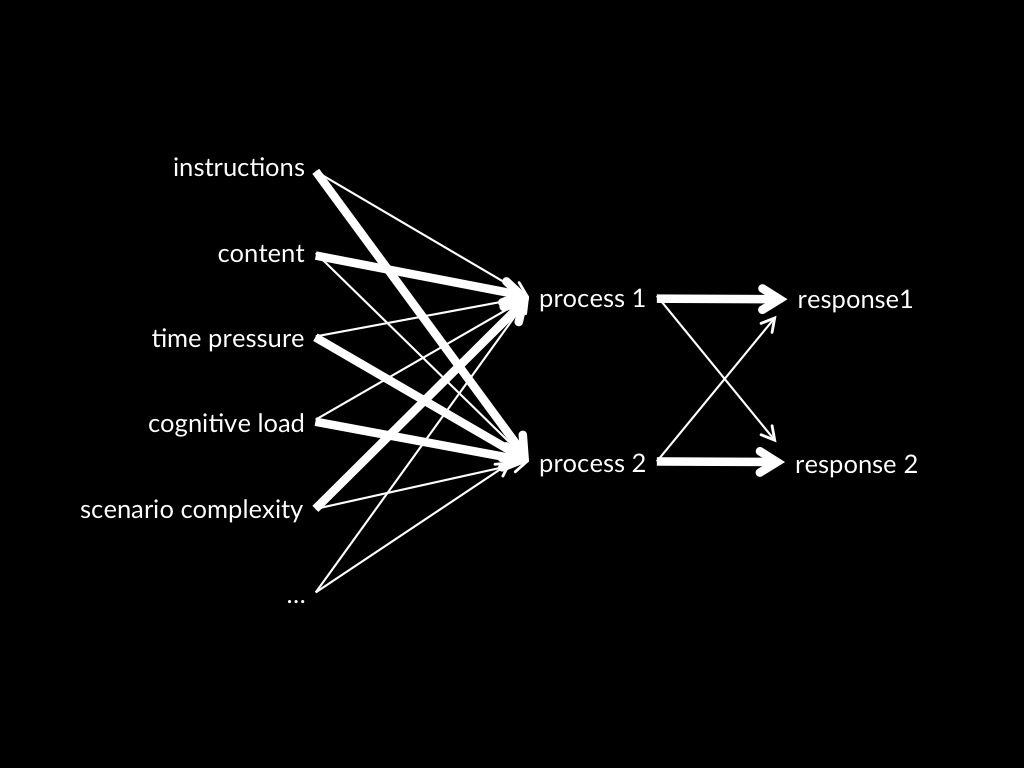

Dual Process Theory (core part)

Two (or more) X-tracking processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

Dual Processes and Development

There are two, or more, processes which involve different models of the domain.

One of these processes first appears early in development, the other later.

The model involved in the early-developing processes does not change over development.

The model involved in the other processes does.

end

Syntax / Innateness

core knowledge of

- physical objects

- [colour]

- mental states

- action

- number

- ...

- The turnip of shapely knowing isn't yet buttressed by death.

- *The buttressed turnip shapely knowing yet isn't of by death.

core knowledge of syntax is innate (?)

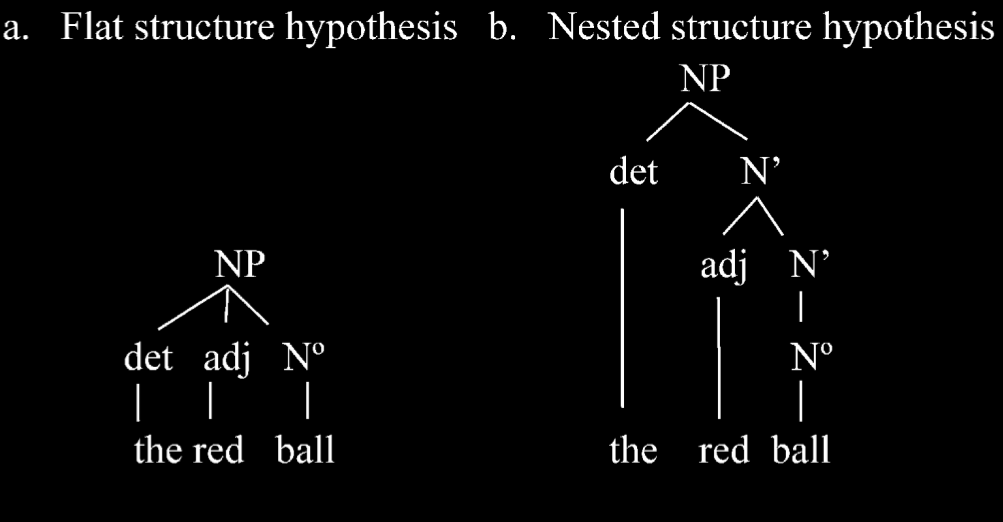

the red ball

‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’

Lidz et al (2003)

- \item ‘red ball’ is a constituent on (b) but not on (a)

- \item anaphoric pronouns can only refer to constituents

- \item In the sentence ‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’, the word ‘one’ is an anaphoric prononun that refers to ‘red ball’ (not just ball). \citep{lidz:2003_what,lidz:2004_reaffirming}.

infants?

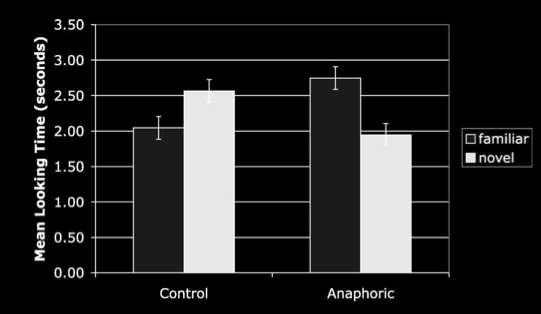

| Look, a yellow bottle! | control: What do you see now? test: Do you see another one? | |

| [yellow bottle] | [yellow bottle] | [blue bottle] |

Lidz et al (2003)

Lidz et al (2003, figure 1)

From 18 months of age or earlier, infants represent the syntax of noun phrases in much the way adults do.

But are these representations innate?

Poverty of stimulus argument

- \itemHuman infants acquire X.

- \itemTo acquire X by data-driven learning you'd need this Crucial Evidence.

- \itemBut infants lack this Crucial Evidence for X.

- \itemSo human infants do not acquire X by data-driven learning.

- \itemBut all acquisition is either data-driven or innately-primed learning.

- \itemSo human infants acquire X by innately-primed learning .

compare Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 18

‘the APS [argument from the poverty of stimulus] still awaits even a single good supporting example’

Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 47

What is innate in humans?

- What evidence is there?

- What does the evidence show is innate?

- Type: knowledge, core knowledge, modules, concepts, abilities, dispositions ...

- Content: e.g. universal grammar, principles of object perception, minimal theory of mind ...

Innateness / Syntax Conclusions

- Adults have inaccessible, domain-specific representations concerning the syntax of natural languages.

- So do infants (from 18 months of age or earlier, well before they can use the syntax in production).

- These representations are a paradigm case of core knowledge.

- These representations plausibly enable understanding and play a key role in the development of abilities to communicate with language.

development as (re)discovery