Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Unperceived Objects: An Illustration

plan

objects

causes

colours

words

non-verbal communications

minds

actions

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

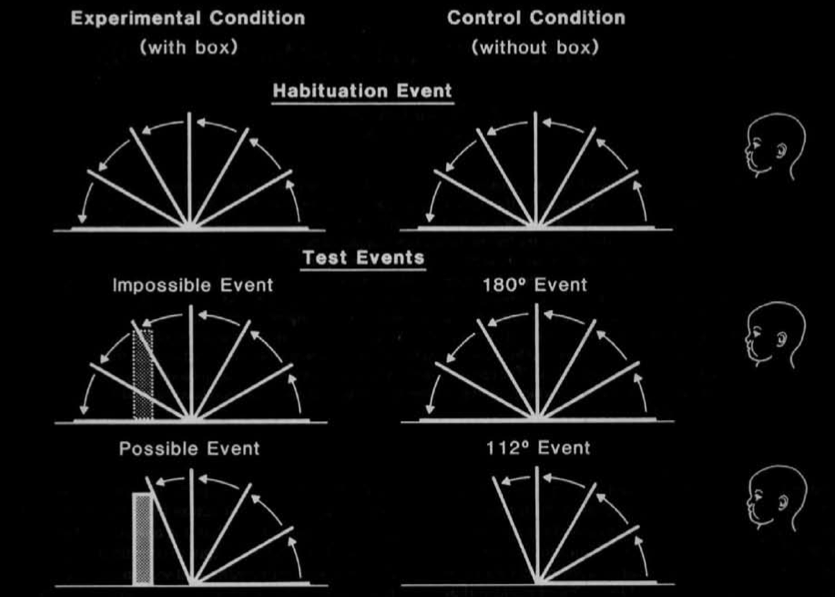

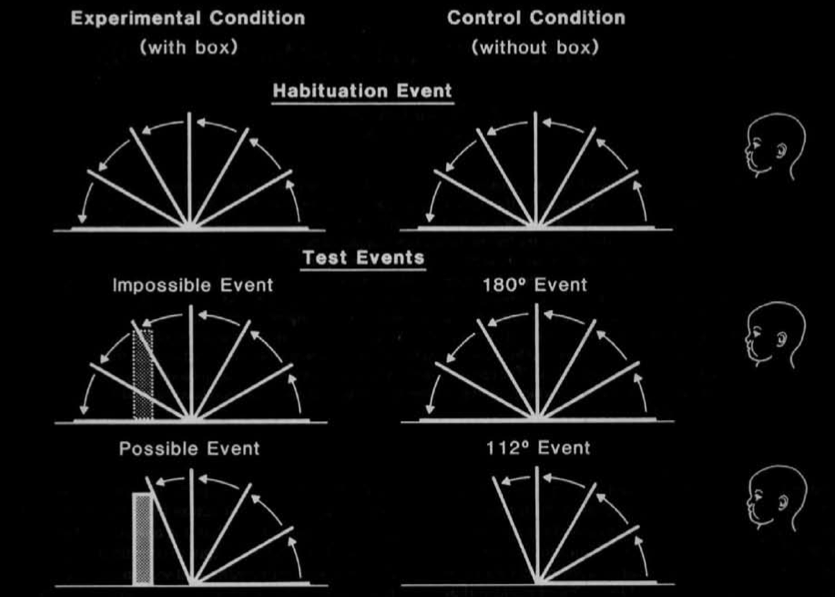

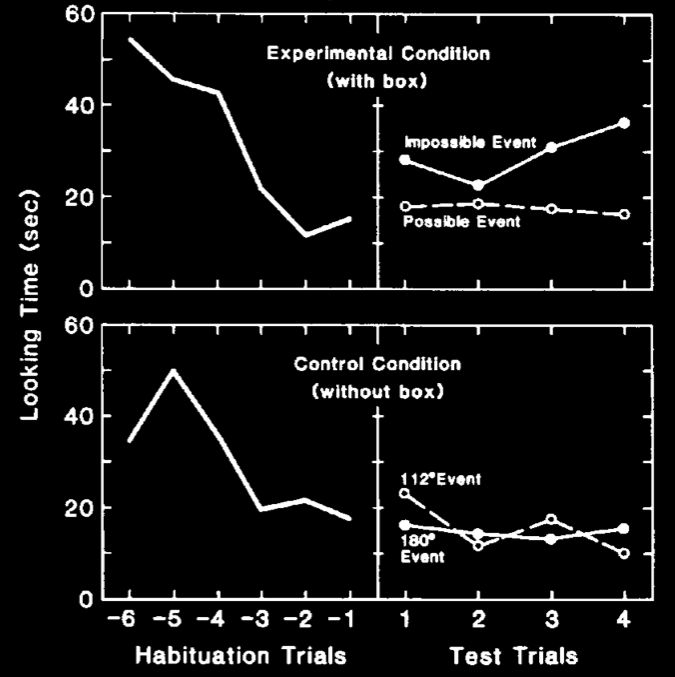

Baillargeon (1987, figure 1)

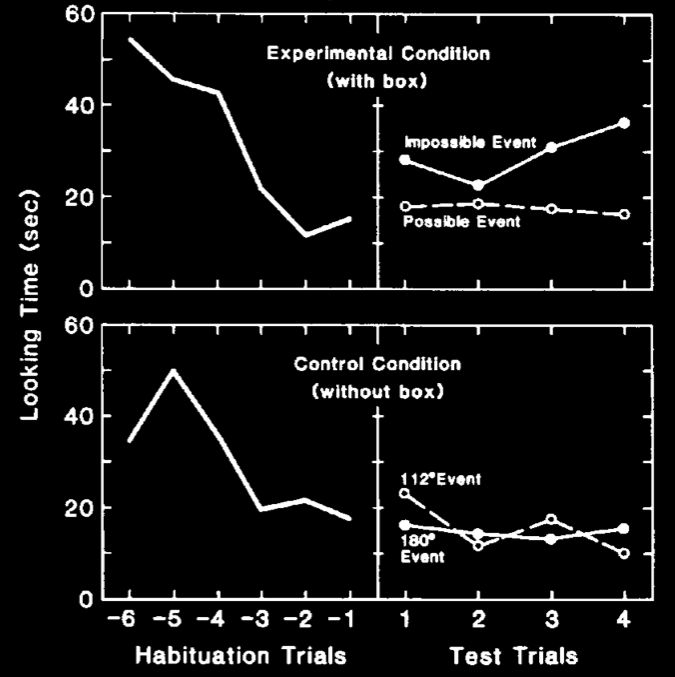

source: Baillargeon et al (1987, figure 2)

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

look: by 4 months of age or earlier (Baillargeon 1987).

look: by around 2.5 months of age or earlier (Aguiar & Baillargeon 1999, Experiment 2)

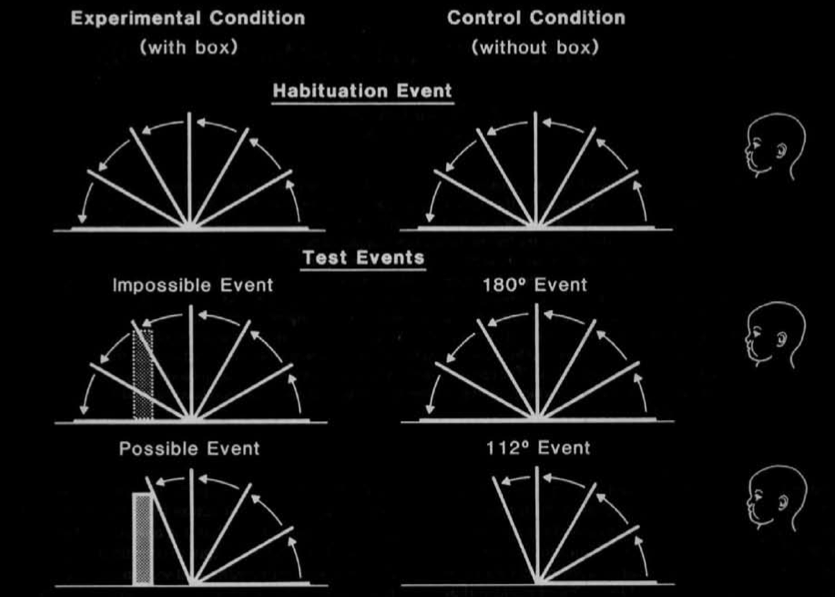

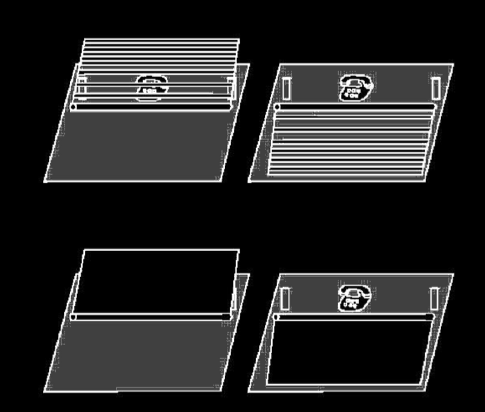

Shinskey and Munakata 2001, figure 1

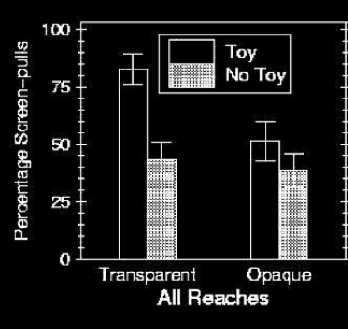

Shinskey and Munakata 2001, figure 2

When do humans first come to know facts about the locations of objects they are not perceiving?

look: by 4 months of age or earlier (Baillargeon 1987).

look: by around 2.5 months of age or earlier(Aguiar & Baillargeon 1999, Experiment 2)

search: not until after 7 months of age (Shinskey & Munakata 2001)

‘action demands are not the only cause of failures on occlusion tasks’

Shinskey (2012, p. 291)

‘the tip of an iceberg’ Charles & Rivera (2009, p. 994)

What is the problem?

Uncomplicated Account of Knowledge

For any given proposition [There’s a spider behind the book] and any given human [Wy] ...

1. Either Wy knows that there’s a spider behind the book, or she does not.

2. Either Wy can act for the reason that there is, or seems to be, a spider behind the book (where this is her reason for acting), or else she cannot.

3. The first alternatives of (1) and (2) are either both true or both false.