Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Social Interaction: Acquiring Your First Words

‘humans acquire knowledge at a pace far outstripping that found in any other species. Recent evidence indicates that interpersonal understanding ... plays a pivotal role in this achievement.’

Baldwin 2000, p. 40

‘the unique aspects of human cognition ... were driven by, or even constituted by, social co-operation.’

Moll & Tomasello 2007, p. 1

How do children acquire their first words?

‘A child learning to speak is learning habits and associations which are just as much determined by the environment as the habit of expecting dogs to bark and cocks to crow’

(Russell 1921, p. 71)

‘[t]he child learns this language from the grown-ups by being trained to its use. I am using the word ‘trained’ in a way strictly analogous to that in which we talk of an animal being trained to do certain things. It is done by means of example, reward, punishment, and suchlike’

(Wittgenstein 1972, p. 77).

‘the child’s early learning of a verbal response depends on society's reinforcement of the response in association with the stimulations that merit the response’

(Quine 1960, p. 82)

infant

stimulations -> utter 'nana'

rat

stimulations -> press lever

‘Crying is the first step toward language when crying is found to procure one or another form of relief or satisfaction. More specific sounds, imitated or not, are rapidly associated with more specific pleasures’

‘there is a rudiment of communication in the simple discovery that sounds produce results. Crying is the first step toward language when crying is found to procure one or another form of relief or satisfaction. More specific sounds, imitated or not, are rapidly associated with more specific pleasures.

(Davidson 2000: 70-1; see also Davidson 1999: 11).

Assumption:

If someone can think, she can communicate with words.

Consequence:

Acquiring words cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire create words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

But:

How do children actually acquire their first words?

children create and creatively adapt words before (and after) learning those of the adults around them

INVESTIGATOR: what is that called?

SHEM: dat's uh vam.

INVESTIGATOR: a vam?

SHEM: yeah.

INVESTIGATOR: why is it called a vam?

SHE: it vams all duh room ups all the water up ...

source: Eve Clark's CHILDES data

(Clark 1982; MacWhinney 2000)

homesigns

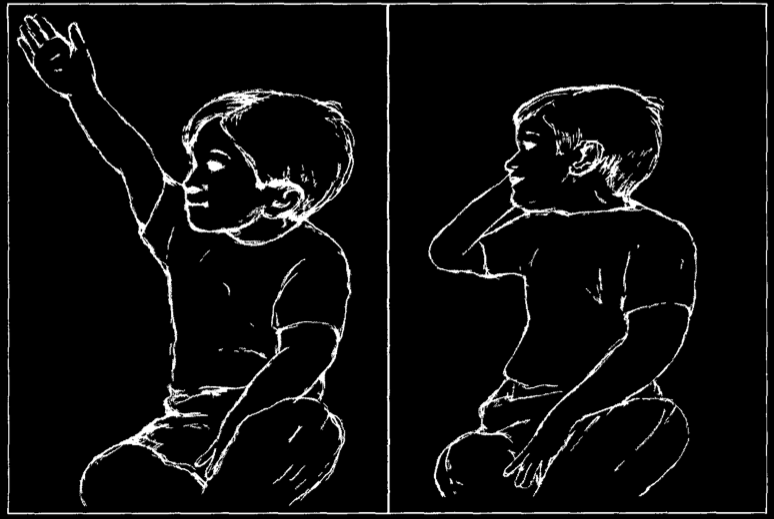

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 1)

Children can create their own languages

with no experience of others' languages

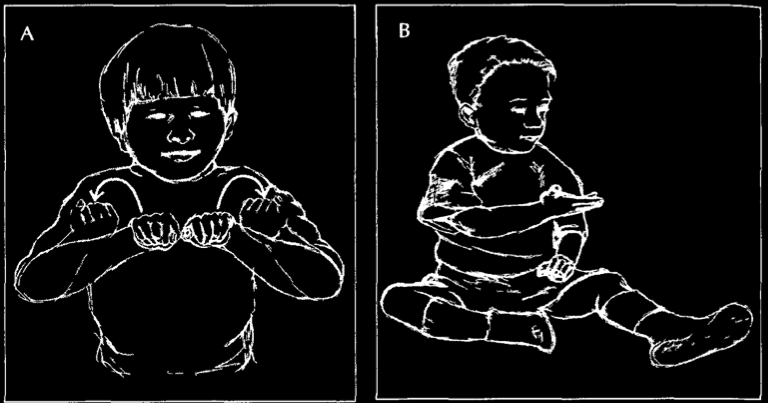

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 2)

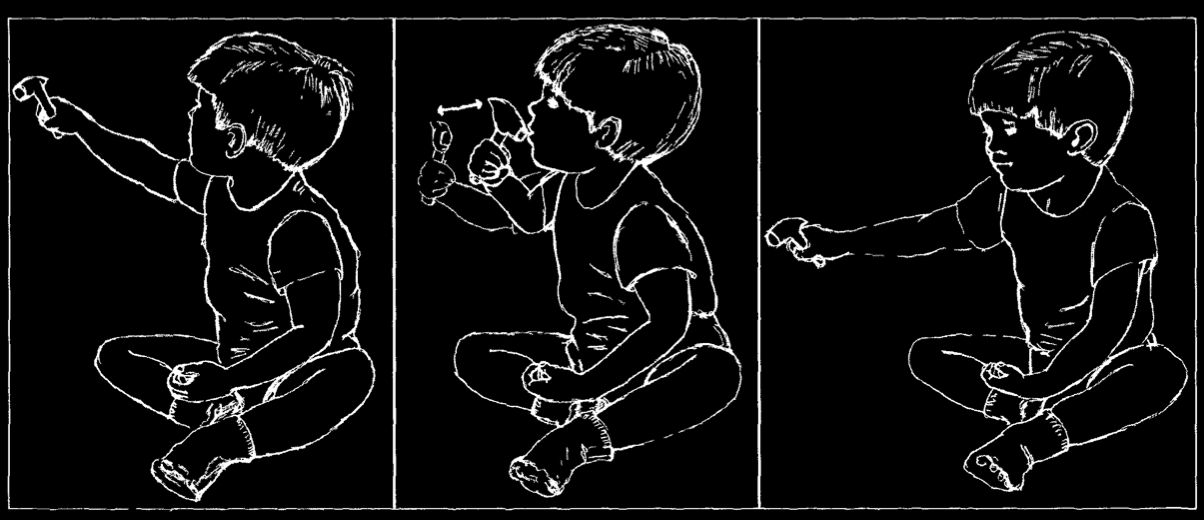

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 11)

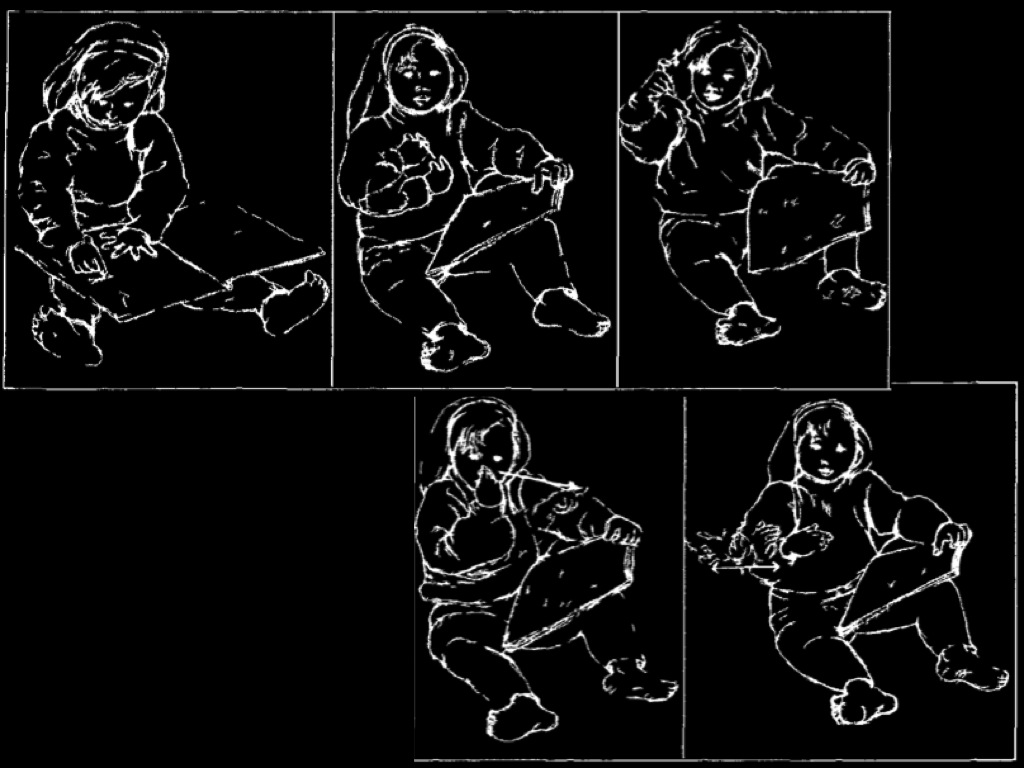

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 22)

Gesture forms are:

- stable

- arbitrary

- systematic

Gesture forms are used:

- with different forces (to ask questions, make comments, request things, ...)

- to talk about past, future and hypothetical things

- to tell stories

- to communicate with oneself

- to talk about gestures (metalanguage)

Goldin-Meadow 2002

social interaction

Assumption:

If someone can think, she can communicate with words.

Consequence:

Acquiring words cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire create words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

But:

How do children actually acquire their first words?