Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Performing vs Understanding Actions in Infancy

Infants use the teleological stance to identify goals.

But does this involve reasoning or motor processes?

Costantini et al, 2012

Needham et al, 2002 / https://news.vanderbilt.edu/files/sticky-mittens.jpg

Sommerville, Woodward and Needham, 2005

Play wearing mittens then observe action.

vs

Observe action then play wearing mittens.

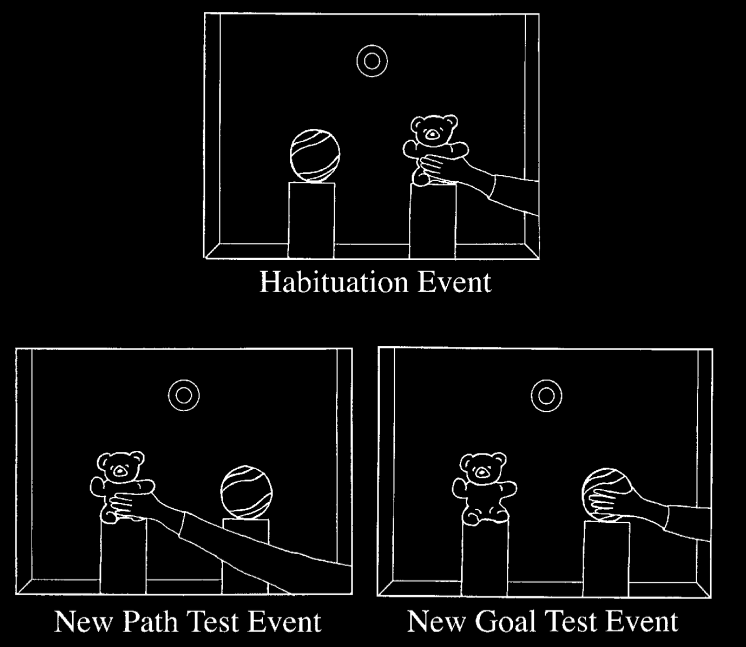

Woodward et al 2001, figure 1

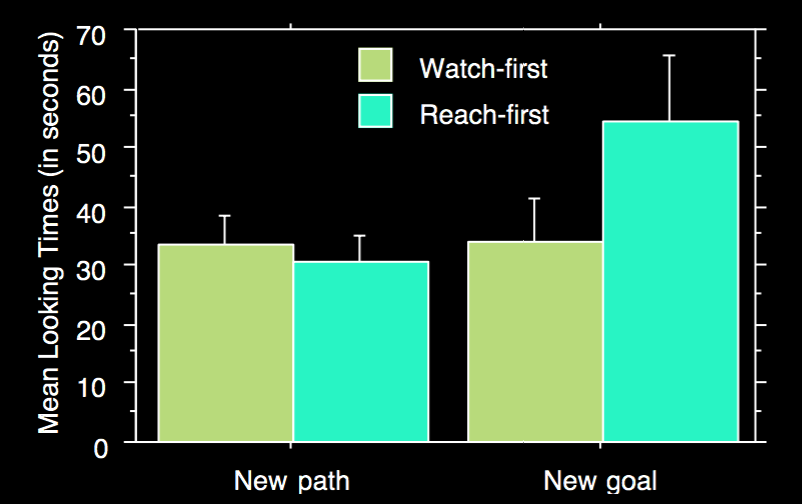

Sommerville, Woodward and Needham, 2005 figure 3

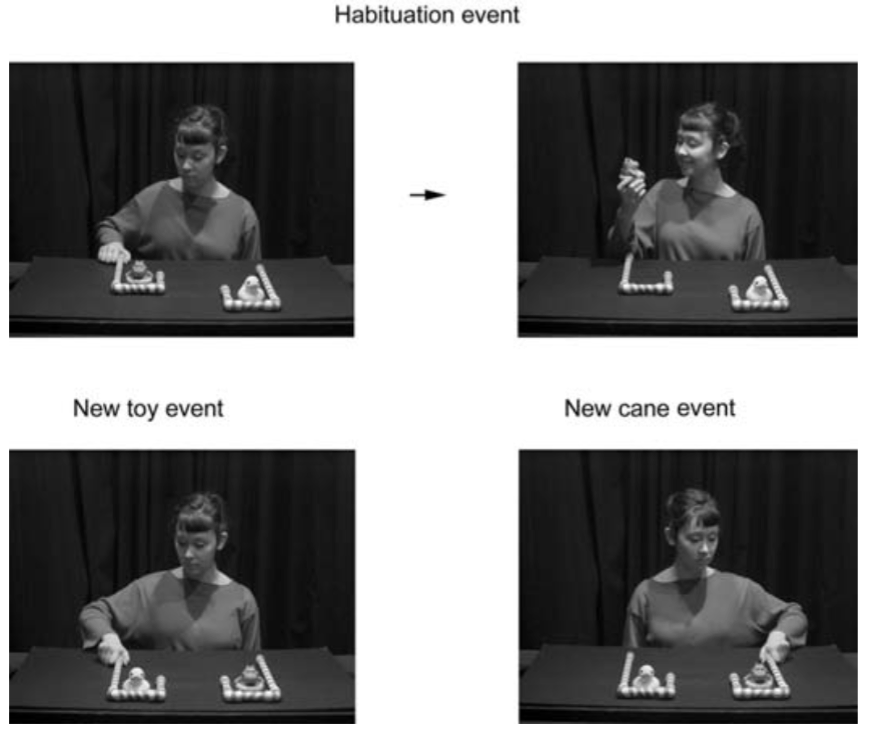

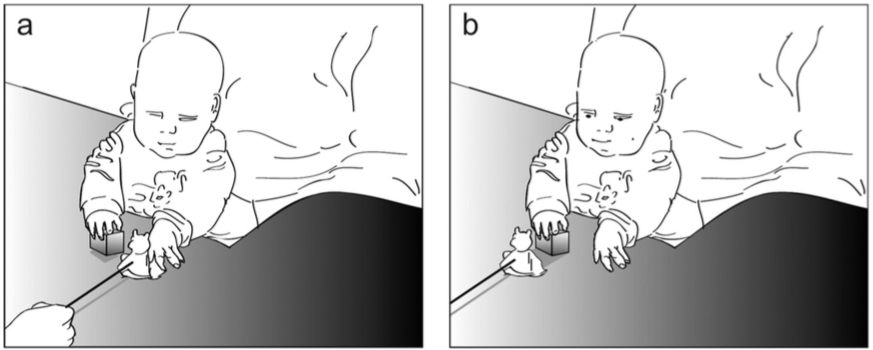

Sommerville et al 2008, figure 1

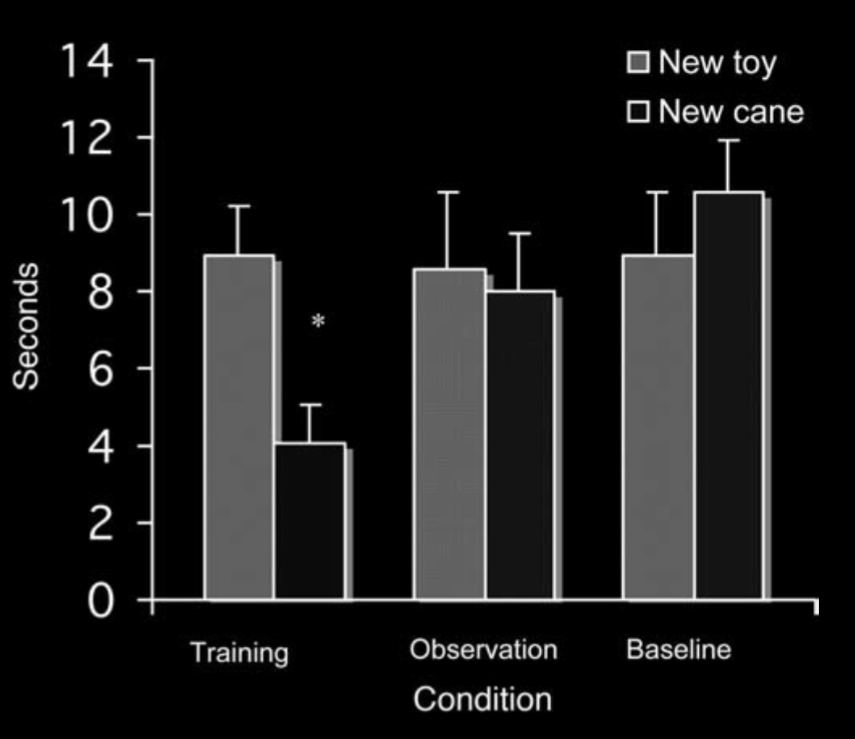

Sommerville et al 2008, figure 2

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 1 (part)

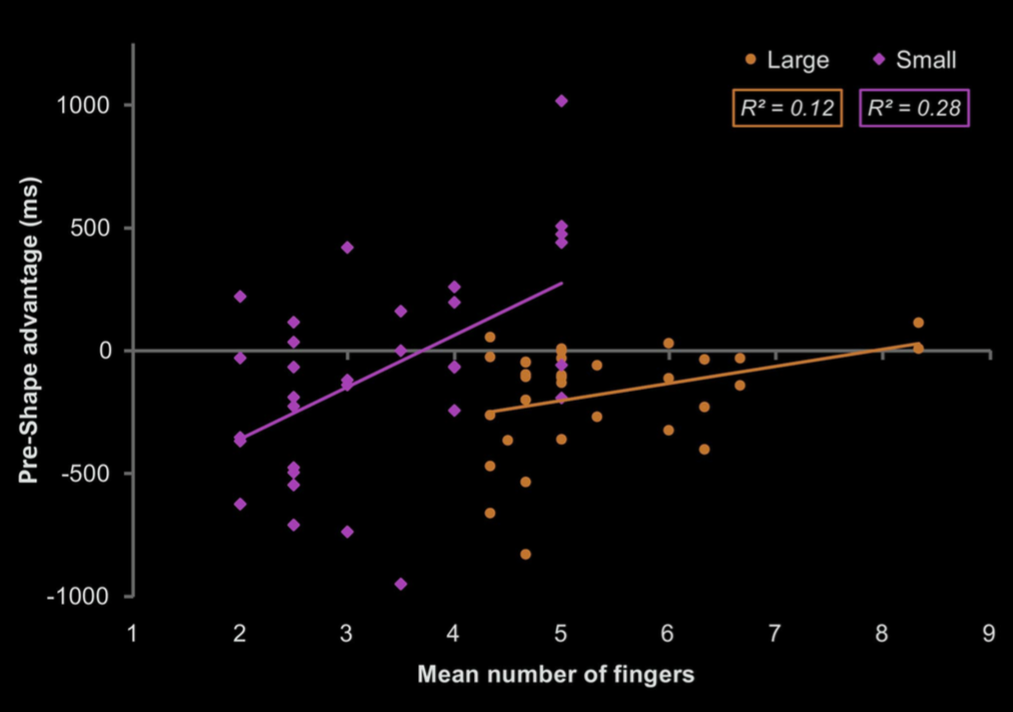

Ambrosini et al, 2013 figure 3

Why?

In infants and adults,

abilities to perform actions enable identifying goals when observing them.

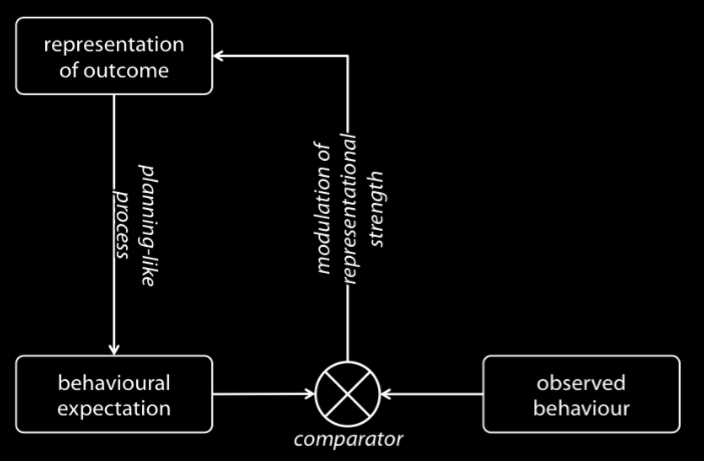

The Motor Theory of Goal Ascription:

goal ascription is acting in reverse

-- in action observation, possible outcomes of observed actions are represented

-- these representations trigger planning as if performing actions directed to the outcomes

-- such planning generates predictions

-- a triggering representation is weakened if its predictions fail

Sinigalia & Butterfill 2015, figure 1

Why?

In infants and adults,

abilities to perform actions enable identifying goals when observing them.

The Teleological Stance

... provides a correct computational description of (some or all) infant (and adult) goal ascription.

But which processes and representations underpin it?

Csibra & Gergeley’s hypothesis: ordinary inference and beliefs

The Motor Theory: motor representations and processes

Evidence

Manipulating abilities to perform actions changes abilities to identify goals.

Adults

- Proactive gaze indicates fast goal ascription.

- The Teleological Stance provides a computational description of the goal ascription underpinning adults’ proactive gaze

- Proactive gaze depends on motor processes and representations: the Motor Theory provides an account of the representations and algorithms.

Infants

- Proactive gaze (from ~12 months) and violation-of-expectations (from ~3 months) indicate goal ascription.

- The Teleological Stance ...

- Two conjectures about algorithms and representations ...

caveat: there’s probably more

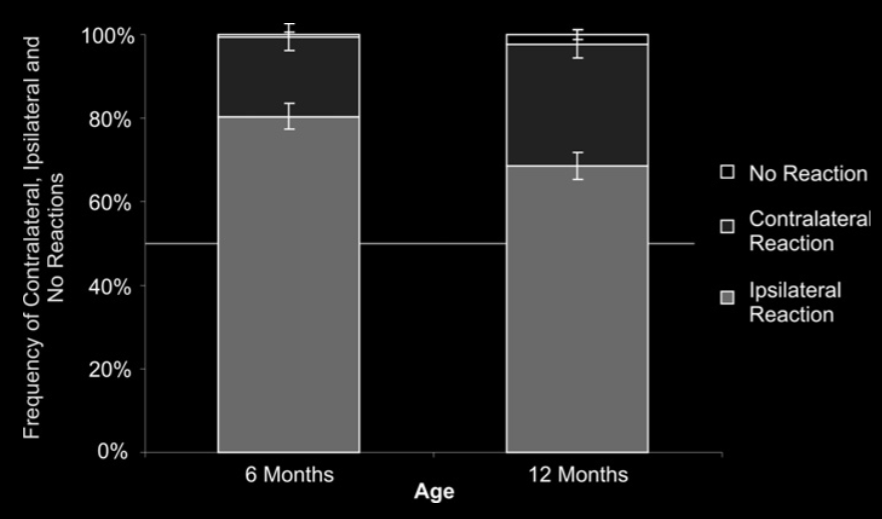

Melzer et al, 2012 figure 1

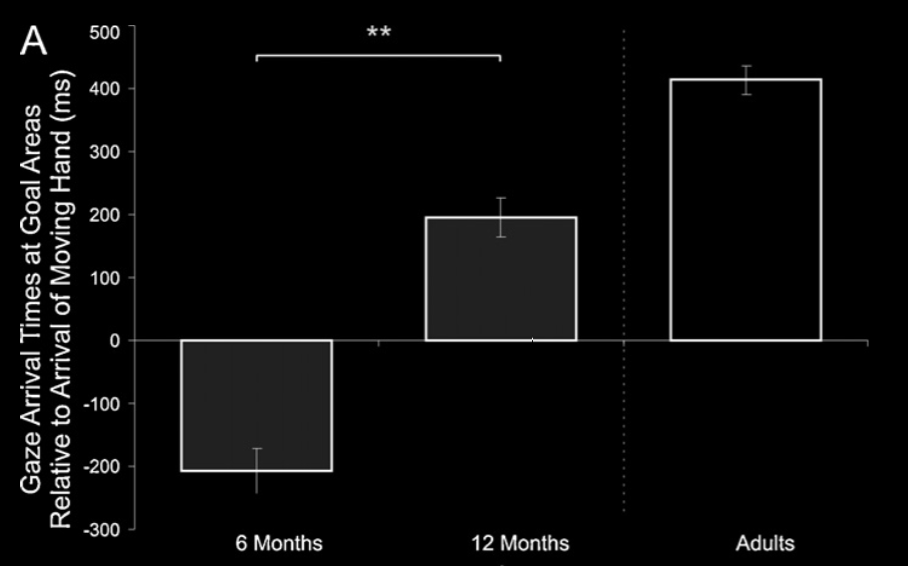

Melzer et al, 2012 figure 3

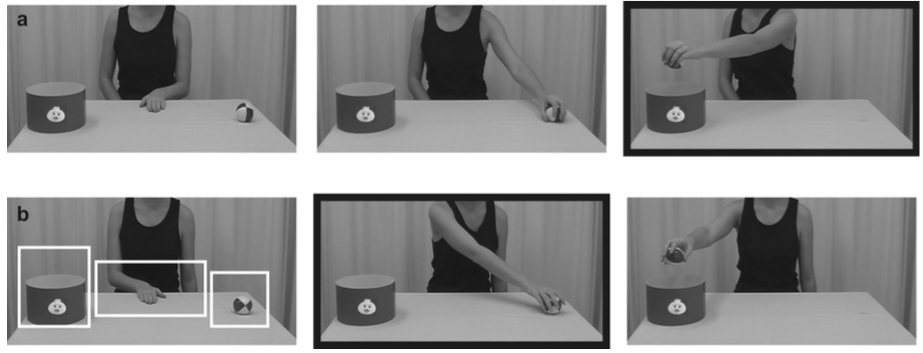

Melzer et al, 2012 figure 2

Melzer et al, 2012 figure 4 (part)