Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Development of Joint Action: Planning

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

‘shared intentional agency [i.e. ‘joint action’] consists, at bottom, in interconnected planning’

Bratman, 2011 p. 11

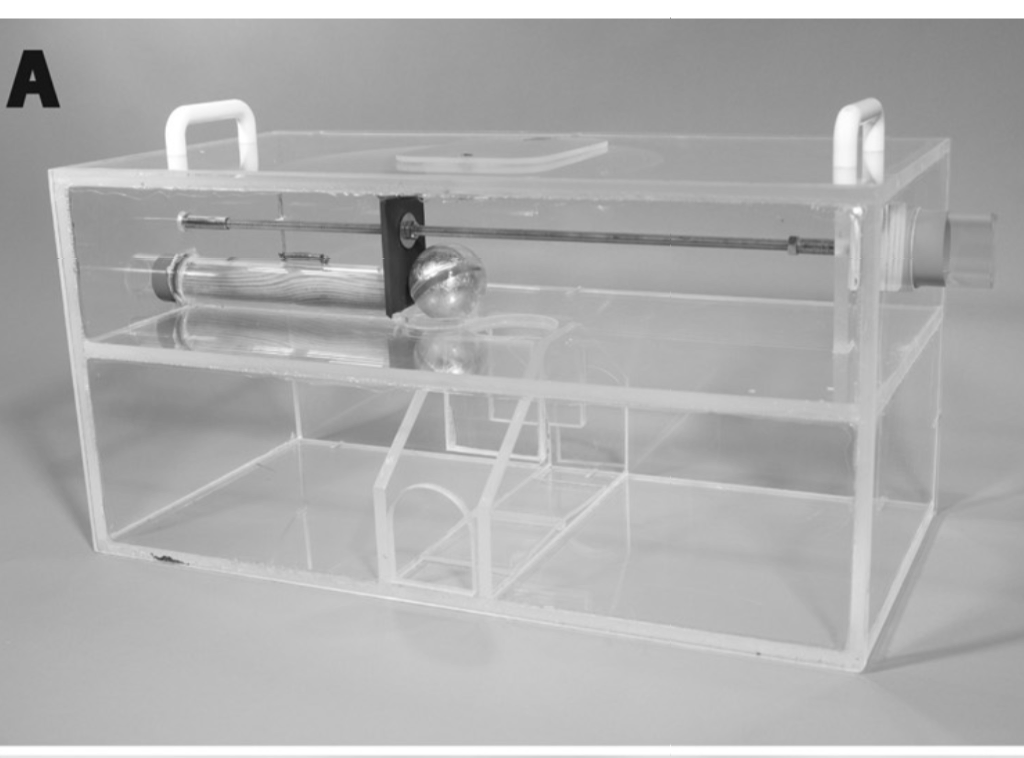

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 1

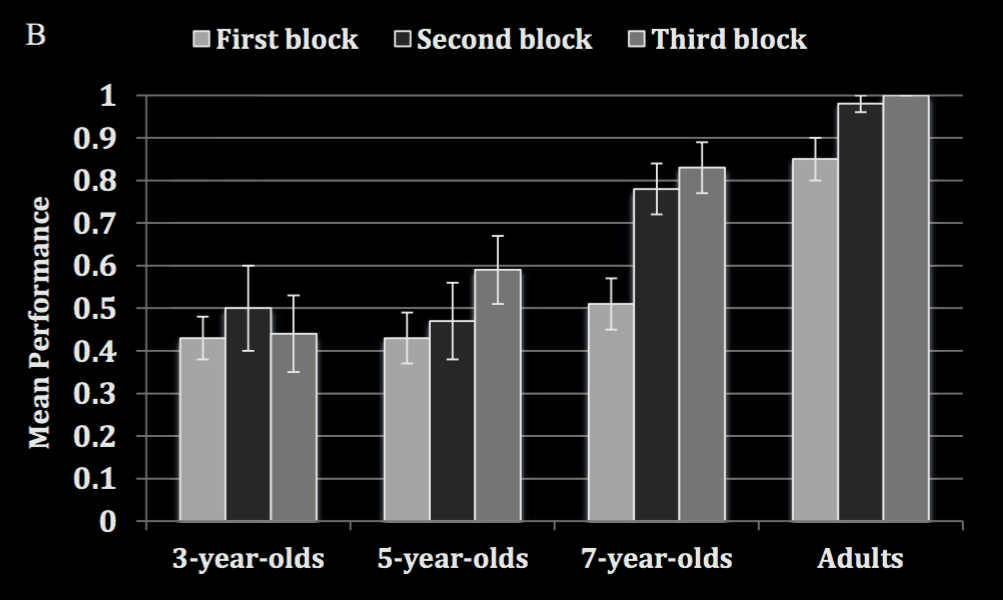

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 2B

‘3- and 5-year-old children do not consider another person’s actions in their own action planning (while showing action planning when acting alone on the apparatus).

Seven-year-old children and adults however, demonstrated evidence for joint action planning. ... While adult participants demonstrated the presence of joint action planning from the very first trials onward, this was not the case for the 7-year-old children who improved their performance across trials.’

Paulus et al, 2016 p. 1059

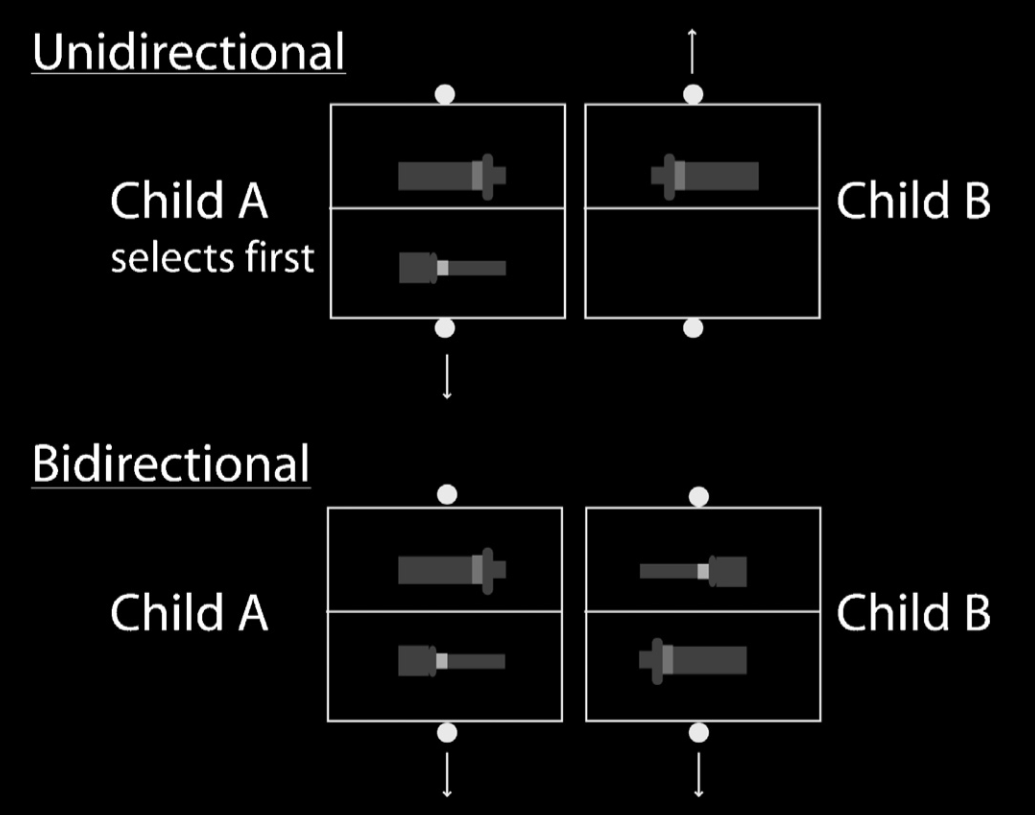

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 1A

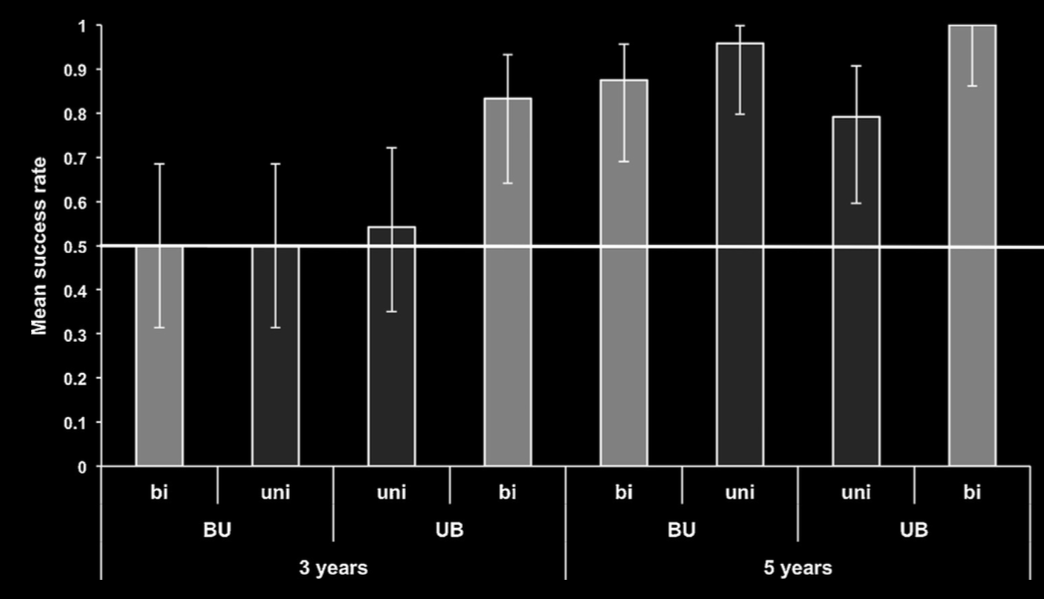

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 2

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 3

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Mismatch:

Bratman’s account of joint action

vs

1- to 3-year-olds’ joint action abilities

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

Inconsistent Triad

1. joint action fosters an understanding of minds;

2. all joint action involves shared intention; and

3. a function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans.