Methods: still face; replay (infants detect whether caregiver reacts, so are

less satisifed with a replay).

\citet[p.~196]{brownell:2011_early} comment: ‘infants become progressively

tuned to the timing and structure of dyadic exchange’

6-12 months

triadic interactions

\citet[p.~197]{brownell:2011_early} comment:

‘adult-infant dyadic interactions expand to include objects, events, and

individuals outside of the dyad (Moore and Dunham 1995)’

~ 12-24 months

infants initiate and re-start joint actions

e.g. ‘peek-a-boo; tickle; rhythmic games; chase’

Brownell, 2011

\citet[p.~197]{brownell:2011_early} comment:

‘Eventually, infants begin themselves to initiate joint action with

adults and to respond in unique ways when adults violate their

expectations for participation in the joint activity. For example, if a

parent becomes distracted during peek-a-boo and fails to take her turn,

12-month olds may try to re-start the game by vocalizing to the adult or

by re- enacting a well-rehearsed part of the game such as placing the

cloth over their own face and waiting. One-year olds also begin to point

to interesting sights and events to share their interest and affect and

they expect adults to respond appropriately by looking (Liszkowski, et al

2006).’

‘infants learn about cooperation by participating in joint action

structured by skilled and knowledgeable interactive partners before they

can represent, understand, or generate it themselves. Cooperative joint

action develops in the context of dyadic interaction with adults in which

the adult initially takes responsibility for and actively structures the

joint activity and the infant progressively comes to master the

structure, timing, and communications involved in the joint action with

the support and guidance of the adult. ... Eager participants from the

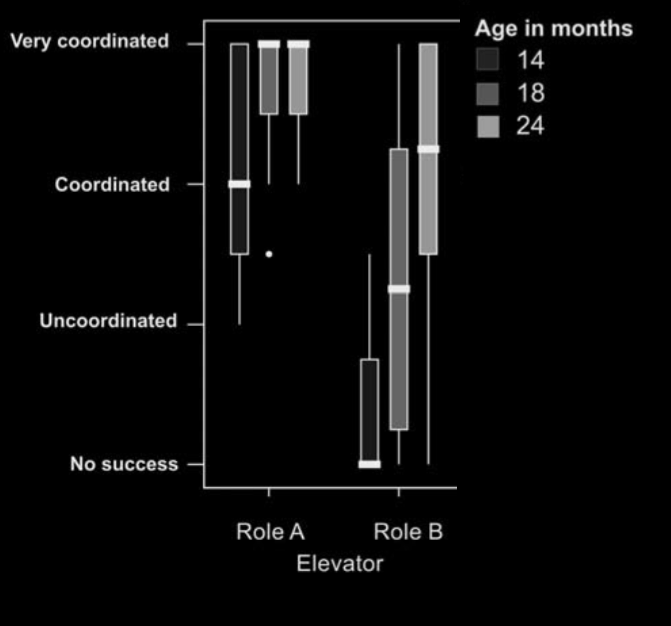

beginning, it takes approximately 2 years for infants to become

autonomous contributors to sustained, goal-directed joint activity as

active, collaborative partners’

\citep[p.~200]{brownell:2011_early}.

‘Without the structure and scaffolding provided by the expert adult

partner, 1-year-old children are unable to generate and sustain joint

action with each other in the service of an external goal. By age two,

however, they can do so readily, even with unfamiliar agemates and on

novel, unfamiliar tasks’

\citep[p.~204]{brownell:2011_early}.